II. THE MAN IN THE MOON.

We must not be misunderstood. By the man in the moon we do not mean any public tavern, or gin-palace, displaying that singular sign. The last inn of that name known to us in London stands in a narrow passage of that fashionable promenade called Regent Street, close to Piccadilly. Nor do we intend by the man in the moon the silvery individual who pays the election expenses, so long as the elector votes his ticket. Neither do we mean the mooney, or mad fellow who is too fond of the cup which cheers and then inebriates; nor even one who goes mooning round the world without a plan or purpose. No; if we are not too scientific, we are too straightforward to be allured by any such false lights as these. By the man in the moon we mean none other than that illustrious personage, whose shining countenance may be beheld many a night, clouds and fogs permitting, beaming good-naturedly on the dark earth, and singing, in the language of a lyric bard,

But some sceptic may assail us with a note of interrogation, saying, "Is there a man in the moon?" "Why, of course, there is!" Those who have misgivings should ask a sailor; he knows, for the punsters assure us that he has been to sea. Or let them ask any lunatic; he should know, for he has been so struck with his acquaintance, that he has adopted the man's name. Or ask any little girl in the nursery, and she will recite, with sweet simplicity, how

The darling may not understand why he sought that venerable city, nor whether he ever arrived there, but she knows very well that

But it is useless to inquire of any stupid joker, for he will idly say that there is no such man there, because, forsooth, a certain single woman who was sent to the moon came back again, which she would never have done if a man had been there with whom she could have married and remained, Nor should any one be misled by those blind guides who darkly hint that it is all moonshine. There is not an Indian moonshee, nor a citizen of the Celestial Empire, some of whose ancestors came from the nocturnal orb, who does not know better than that. Perhaps the wisest course is to inquire within. Have not we all frequently affirmed that we knew no more about certain inscrutable matters than the man in the moon? Now we would never have committed ourselves to such a comparison had we not been sure that the said man was a veritable and creditable, though somewhat uninstructed person. But our feelings ought not to be wrought upon in this way. We "had rather be a dog, and bay the moon, than such a Roman" as is not at least distantly acquainted with that brilliant character in high life who careers so conspicuously amid the constellations which constitute the upper ten thousand of super-mundane society. And now some inquisitive individual may be impatient to interrupt our eloquence with the question, "What are you going to make of the man in the moon?" Well, we are not going to make anything of him. For, first, he is a man; therefore incapable of improvement. Secondly, he is in the moon, and that is out of our reach. *7 All that we can promise

*7 Besides, as old John Lilly says in the prologue to his Endymion(1591), "There liveth none under the sunne, that knows what to make of the man in the moone.

just now is, to furnish a few particulars of the man himself; some account of calls which he is reported to have made to his friends here below; and also some account of visits which his friends on earth have paid him in return.

We know something of his residence, whenever he is at home: what do we know of the man? We have been annoyed at finding his lofty name desecrated to base uses. If "imagination may trace the noble dust of Alexander, till he find it stopping a bung-hole," literature traces the man in the moon, and discovers him pressed into the meanest services. Our readers need not be disquieted with details; though our own equanimity has been sorely disturbed as we have seen scribblers dragging from the skies a "name at which the world grows pale, to point a moral, or adorn a tale." Political squibs, paltry chapbooks, puny satires, and penny imbecilities, too numerous for mention here, with an occasional publication of merit, have been printed and sold at the expense of the man in the moon. For the sake of the curious we place the titles and dates of some of these in an appendix and pass on. We have not learned very many particulars relating to the domestic habits or personal character of the man in the moon, consequently our smallest biographical contributions will be thankfully received. We must not be pressed for his photograph, at present. We certainly wish it could have been procured; but though photography has taken some splendid views of the

"If Cæsar can hide the sun with a blanket, or put the moon in his pocket, we will pay him tribute for light" (Cymbeline).

face of the moon, it has not yet produced any perfect picture of the physiognomy of the man. It should always be borne in mind that, as Stilpo says in the old play of Timon, written about 1600, "The man in the moone is not in the moone superficially, although he bee in the moone (as the Greekes will have it) catapodially, specificatively, and quidditatively." 4 This beautiful language, let us explain for the behoof of any foreign reader, simply means that he is not always where we can get at him; and therefore his venerable visage is missing from our celestial portrait gallery. One fact we have found out, which we fear will ripple the pure water placidity of some of our best friends; but the truth must be told.

Another old ballad runs:

In a Jest Book of the Seventeenth Century we came across the following story: "A company of gentlemen coming into a tavern, whose signe was the Moone, called for a quart of sacke. The drawer told them they had none; whereat the gentlemen wondring were told by the drawer that the man in the moon always drunke claret." 6 Several astronomers assert the absence of water in the moon; if this be the case, what is the poor man to drink? Still, it is an unsatisfactory announcement to us all; for we are afraid that it is the claret which makes him look so red in the face sometimes when he is full, and gets a little fogged. We have ourselves seen

him actually what sailors call "half-seas over," when we have been in mid-Atlantic. We only hope that he imbibes nothing stronger, though it is said that moonlight is but another name for smuggled spirits. The lord of Cynthia must not be too hastily suspected, for, at most, the moon fills her horn but once a month. Still, the earth itself being so invariably sober, its satellite, like Cæsar's wife, should be above suspicion. We therefore hope that our lunar hero may yet take a ribbon of sky-blue from the milky way, and become a staunch abstainer; if only for example's sake.

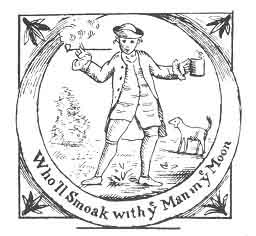

Some old authors and artists have represented the

man in the moon as an inveterate smoker, which habit surprises us, who supposed him to be

as the magnificent Milton has it. His tobacco must be bird's-eye, as he takes a bird's-eye view of things; and his pipe is presumably a meer-sham, whence his "sable clouds turn forth their silver lining on the night." Smoking, without doubt, is a bad practice, especially when the clay is choked or the weed is worthless; but fuming against smokers we take to be infinitely worse.

We are better pleased to learn that the man in the moon is a poet. Possibly some uninspired groveller, who has never climbed Parnassus, nor drunk of the Castalian spring, may murmur that this is very likely, for that all poetry is "moonstruck madness." Alas if such an antediluvian barbarian be permitted to "revisit thus the glimpses of the moon, making night hideous" as he mutters his horrid blasphemy! We, however, take a nobler view of the matter. To us the music of the spheres is exalting as it is exalted; and the music of earth is a "sphere-descended maid, friend of pleasure, wisdom's aid." We are therefore disposed to hear the following lines, which have been handed down for publication. Their title is autobiographical, and, for that reason, they are slightly egotistical.

"A SHREWD OLD FELLOW'S THE MAN IN THE MOON."

This effusion is not excessively flattering to our "great globe," and "all which it inherit"; and we surmise that the author was in a misanthropic mood when it was written. Yet it is serviceable sometimes to see ourselves as others see us. On the other hand, we have but little liking for those who "hope to merit heaven by making earth a hell," in any sense. We prefer to believe that the tide is rising though the waves recede, and that our dark world is waxing towards the full-orbed glory "to which the whole creation moves."

Here for the present we part company with the man in the moon as material for amusement, that we may track him through the mythic maze, where, in well-nigh every language, he has left some traces of his existence. As there is a side of the moon which we have never seen, and according to Laplace never shall see, there is also an aspect of the matter in hand that remains to be traversed, if we would circumambulate its entire extent. Our subject must now be viewed in the magic mirror of mythology. The antiquarian Ritson shall state the question to be brought before our honourable house of inquiry. He denominates the man in the moon "an imaginary being, the subject of perhaps one of the most ancient, as well as one of the most popular, superstitions of the world." 8 And as we must explore the vestiges of antiquity, Asiatic and European, African and American, and even Polynesian, we bespeak patient forbearance and attention. One little particular we may partly clear up at once, though it will meet us again in another connection. It will serve as a sidelight to our legendary scenes. In English, French, Italian, Latin, and Greek, the moon is feminine; but in all the Teutonic tongues the moon is masculine. Which of the twain is its true gender? We go back to the Sanskrit for an answer. Professor Max Müller rightly says, "It is no longer denied that for throwing light on some of the darkest problems that have to be solved by the student of language, nothing is so useful as a critical study of Sanskrit." 9Here the word for the moon is mâs, which is masculine. Mark how even what Hamlet calls "words, words, words"

lend their weight and value to the adjustment of this great argument. The very moon is masculine, and, like Wordsworth's child, is "father of the man."

If a bisexous moon seem an anomaly, perhaps the suggestion of Jamieson will account for the hermaphrodism: "The moon, it has been said, was viewed as of the masculine gender in respect of the earth, whose husband he was supposed to be; but as a female in relation to the sun, as being his spouse." 10 Here, also, we find a clue to the origin of this myth. If modern science, discovering the moon's inferiority to the sun, call the former feminine, ancient nescience, supposing the sun to be inferior to the moon, called the latter masculine. The sun, incomparable in splendour, invariable in aspect and motion, to the unaided eye immaculate in surface, too dazzling to permit prolonged observation, and shining in the daytime, when the mind was occupied with the duties of pastoral, agricultural, or commercial life, was to the ancient simply an object of wonder as a glory, and of worship as a god. The moon, on the contrary, whose mildness of lustre enticed attention, whose phases were an embodiment of change, whose strange spots seemed shadowy pictures of things and beings terrestrial, whose appearance amid the darkness of night was so welcome, and who came to men susceptible, from the influences of quiet and gloom, of superstitious imaginings, from the very beginning grew into a familiar spirit of kindred form with their own, and though regarded as the subordinate and

wife of the sun, was reverenced as the superior and husband of the earth. With the transmission of this myth began its transmutation. From the moon being a man, it became a man's abode: with some it was the world whence human spirits came; with others it was the final home whither human spirits returned. Then it grew into a penal colony, to which egregious offenders were transported; or prison cage, in which, behind bars of light, miserable sinners were to be exposed to all eternity, as a warning to the excellent of the earth. One thing is certain, namely, that, during some phases, the moon's surface strikingly resembles a man's countenance. We usually represent the sun and the moon with the faces of men; and in the latter case the task is not difficult. Some would say that the moon is so drawn to reproduce some lunar deity: it would be more correct to say that the lunar deity was created through this human likeness. Sir Thomas Browne remarks, "The sun and moon are usually described with human faces: whether herein there be not a pagan imitation, and those visages at first implied Apollo and Diana, we may make some doubt." 11 Brand, in quoting Browne, adds, "Butler asks a shrewd question on this head, which I do not remember to have seen solved:--

Another factor in the formation of our moon-myth was the anthropomorphism which sees something manlike in everything, not only in the anthropoid apes, where we may find a resemblance more faithful than flattering, but also in the mountains and hills, rivers and seas of earth, and in the planets and constellations of heaven. Anthropomorphism was but a species of personification, which also metamorphosed the firmament into a menagerie of lions and bears, with a variety of birds, beasts, and fishes. Dr. Wagner writes: "The sun, moon, and stars, clouds and mists, storms and tempests, appeared to be higher powers, and took distinct forms in the imagination of man. As the phenomena of nature seemed to resemble animals either in outward form or in action, they were represented under the figure of animals." 13 Sir George W. Cox points out how phrases ascribing to things so named the actions or feelings of living beings, "would grow into stories which might afterwards be woven together, and so furnish the groundwork of what we call a legend or a romance. This will become plain, if we take the Greek sayings or myths about Endymion and Selênê. Here, besides these two names, we have the names Protogenia and Asterodia. But every Greek knew that Selênê was a name for the moon, which was also described as Asterodia because she has her path among the stars, and that Protogenia denoted the first or early born morning. Now Protogenia was the mother of Endymion, while Asterodia was his wife; and so far the

names were transparent. Had all the names remained so, no myth, in the strict sense of the word, could have sprung up; but as it so happened, the meaning of the name Endymion, as denoting the sun, when he is about to plunge or dive into the sea, had been forgotten, and thus Endymion became a beautiful youth with whom the moon fell in love, and whom she came to look upon as he lay in profound sleep in the cave of Latmos." 14 To this growth and transformation of myths we may return after awhile; meanwhile we will follow closely our man in the moon, who, among the Greeks, was the young Endymion, the beloved of Diana, who held the shepherd passionately in her embrace. This fable probably arose from Endymion's love of astronomy, a predilection common in ancient pastors. He was, no doubt, an ardent admirer of the moon; and soon it was reported that Selênê courted and caressed him in return. May such chaste enjoyment be ours also! We may remark, in passing, that classic tales are pure or impure, very much according to the taste of the reader. "To the jaundiced all things seem yellow," say the French; and Paul said, "To the pure all things are pure: but unto them that are defiled is nothing pure." According to Serapion, as quoted by Clemens Alexandrinus, the tradition was that the face which appears in the moon is the soul of a Sibyl. Plutarch, in his treatise, Of the Face appearing in the roundle of the Moone, cites the poet Agesinax as saying of that orb,

The story of the man in the moon as told in our British nurseries is supposed to be founded on Biblical fact. But though the Jews have a Talmudic tradition that Jacob is in the moon, and though they believe that his face is plainly visible, the Hebrew Scriptures make no mention of the myth. Yet to our fireside auditors it is related that a man was found by Moses gathering sticks on the Sabbath, and that for this crime he was transferred to the moon, there to remain till the end of all things. The passage cited in support of this tale is Numbers xv. 32-36. Upon referring to the sacred text, we certainly find a man gathering sticks upon the Sabbath day, and the congregation gathering stones for his merciless punishment, but we look in vain for any mention of the moon. Non est inventus. Of many an ancient story-teller we may say, as Sheridan said of Dundas, "the right honourable gentleman is indebted to his memory for his jests and to his imagination for his facts."

Mr. Proctor reminds us that "according to German nurses, the day was not the Sabbath, but Sunday. Their tale runs as follows: Ages ago there went one Sunday an old man into the woods to hew sticks. He

cut a faggot and slung it on a stout staff, cast it over his shoulder, and began to trudge home with his burthen. On his way he met a handsome man in Sunday suit, walking towards the church. The man stopped, and asked the faggot-bearer, 'Do you know that this is Sunday on earth, when all must rest from their labours?' 'Sunday on earth, or Monday in heaven, it's all one to me!' laughed the woodcutter. 'Then bear your bundle for ever!' answered the stranger. 'And as you value not Sunday on earth, yours shall

be a perpetual moon-day in heaven; you shall stand for eternity in the moon, a warning to all Sabbath-breakers.' Thereupon the stranger vanished, and the man was caught up with his staff and faggot into the moon, where he stands yet." 16

In Tobler's account the man was given the choice of burning in the sun, or of freezing in the moon; and preferring a lunar frost to a solar furnace, he is to be seen at full moon seated with his bundle of sticks on his back. If "the cold in clime are cold in blood," we may be thankful that we do not hibernate eternally

in the moon and in the nights of winter, when the cold north winds blow," we may look up through the casement and "pity the sorrows of this poor old man."

Mr. Baring-Gould finds that "in Schaumberg-lippe, the story goes, that a man and a woman stand in the moon: the man because he strewed brambles and thorns on the church path, so as to hinder people from attending mass on Sunday morning; the woman because she made butter on that day. The man carries his bundle of thorns, the woman her butter tub. A similar tale is told in Swabia and in Marken. Fischart says that there 'is to be seen in the moon a mannikin who stole wood'; and Prætorius, in his description of the world, that 'superstitious people assert that the black flecks in the moon are a man who gathered wood on a Sabbath, and is therefore turned into stone.'" 17

The North Frisians, among the most ancient and pure of all the German tribes, tell the tale differently. "At the time when wishing was of avail, a man, one Christmas Eve, stole cabbages from his neighbour's garden. When just in the act of walking off with his load, he was perceived by the people, who conjured (wished) him up in the moon. There he stands in the full moon, to be seen by everybody, bearing his load of cabbages to all eternity. Every Christmas Eve he is said to turn round once. Others say that he stole willow-boughs, which he must bear for ever. In Sylt the story goes that he was a sheep-stealer, that enticed

sheep to him with a bundle of cabbages, until, as an everlasting warning to others, he was placed in the moon, where he constantly holds in his hand a bundle of cabbages. The people of Rantum say that he is a giant, who at the time of the flow stands in a stooping posture, because he is then taking up water, which he pours out on the earth, and thereby causes the flow; but at the time of the ebb he stands erect and rests from his labour, when the water can subside again." 18

Crossing the sea into Scandinavia, we obtain some valuable information. First, we find that in the old Norse, or language of the ancient Scandinavians, the sun is always feminine, and the moon masculine. In the Völu-Spá, a grand, prophetic poem, it is written--

We also learn that "the moon and the sun are brother and sister; they are the children of Mundilföri, who, on account of their beauty, called his son Mâni, and his daughter Sôl." Here again we observe that the moon is masculine." Mini directs the course of the moon, and regulates Nyi (the new moon) and Nithi (the waning moon). He once took up two children from the earth, Bil and Hiuki, as they were going from the well of Byrgir, bearing on their shoulders the

bucket Sœg, and the pole Simul." 20 These two children, with their pole and bucket, were placed in the moon, "where they could be seen from earth"; which phrase must refer to the lunar spots. Thorpe, speaking of the allusion in the Eddato these spots, says that they "require but little illustration. Here they are children carrying water in a bucket, a superstition still preserved in the popular belief of the Swedes." 21 We are all reminded at once of the nursery rhyme--

Little have we thought, when rehearsing this jingle in our juvenile hours, that we should some day discover its roots in one of the oldest mythologies of the world. But such is the case. Mr. Baring-Gould has evolved the argument in a manner which, if not absolutely conclusive in each point, is extremely cogent and clear. "This verse, which to us seems at first sight nonsense, I have no hesitation in saying has a high antiquity, and refers to the Eddaic Hjuki and Bil. The names indicate as much. Hjuki, in Norse, would be pronounced Juki, which would readily become Jack; and Bil, for the sake of euphony and in order to give a female name to one of the children, would become Jill. The fall of Jack, and the subsequent fall of Jill, simply represent the vanishing of one moon spot after another, as the moon wanes. But the old Norse myth had a deeper signification

than merely an explanation of the moon spots. Hjuki is derived from the verb jakka, to heap or pile together, to assemble and increase; and Bil, from bila, to break up or dissolve. Hjuki and Bil, therefore, signify nothing more than the waxing and waning of the moon, and the water they are represented as bearing signifies the fact that the rainfall depends on the phases of the moon. Waxing and waning were individualized, and the meteorological fact of the connection of the rain with the moon was represented by the children as water-bearers. But though Jack and Jill became by degrees dissevered in the popular mind from the moon, the original myth went through a fresh phase, and exists still under a new form. The Norse superstition attributed theft to the moon, and the vulgar soon began to believe that the figure they saw in the moon was the thief. The lunar specks certainly may be made to resemble one figure, but only a lively imagination can discern two. The girl soon dropped out of popular mythology, the boy oldened into a venerable man, he retained his pole, and the bucket was transformed into the thing he had stolen--sticks or vegetables. The theft was in some places exchanged for Sabbath-breaking, especially among those in Protestant countries who were acquainted with the Bible story of the stick-gatherer." 22

The German Grimm, who was by no means a grim German, but a very genial story-teller, also maintains this transformation of the original myth." Plainly enough the water-pole of the heathen story has been

transformed into the axe's shaft, and the carried pail into the thornbush; the general idea of theft was retained, but special stress laid on the keeping of the Christian holiday, the man suffers punishment not so much for cutting firewood, as because he did it on a Sunday." 23 Manifestly "Jack and Jill went up the hill" is more than a Runic rhyme, and like many more of our popular strains might supply us with a most interesting and instructive entertainment; but we must hasten on with the moon-man.

We come next to Britain. Alexander Neckam, a learned English abbot, poet, and scholar, born in St. Albans, in 1157, in commenting on the dispersed shadow in the moon, thus alluded to the vulgar belief: "Nonne novisti quid vulgus vocet rusticum in luna portantem spinas? Unde quidam vulgariter loquens ait,

This may be rendered, "Do you not know what the people call the rustic in the moon who carries the thorns? Whence one vulgarly speaking says,

Thomas Wright considers Neckam's Latin version of this popular distich "very curious, as being the

earliest allusion we have to the popular legend of the man in the moon." We are specially struck with the reference to theft; while no less noteworthy is the absence of that sabbatarianism, which is the "moral" of the nursery tale.

In the British Museum there is a manuscript of English poetry of the thirteenth century, containing an old song composed probably about the middle of that century. It was first printed by Ritson in his Ancient Songs, the earliest edition of which was published in London, in 1790. The first lines are as follows:

In the Archæological Journal we are presented with a relic from the fourteenth century. "Mr. Hudson Taylor submitted to the Committee a drawing of an impression of a very remarkable personal seal, here

represented of the full size. It is appended to a deed (preserved in the Public Record Office) dated in the ninth year of Edward the Third, whereby Walter de Grendene, clerk, sold to Margaret, his mother, one messuage, a barn and four acres of ground in the parish of Kingston-on-Thames. The device appears to be founded on the ancient popular legend that a husbandman who had stolen a bundle of thorns from a hedge was, in punishment of his theft, carried up to the moon. The legend reading Te Waltere docebo cur spinas phebo gero, 'I will teach you, Walter, why I carry thorns in the moon,' seems to be an enigmatical mode of expressing the maxim that honesty is the best policy." 26

About fifty years later, in the same century, Geoffrey Chaucer, in his Troylus and Creseide adverts to the subject in these lines:

And in another place he says of Lady Cynthia, or the moon:

Whether Chaucer wrote the Testament and Complaint of Creseide, in which these latter lines occur, is doubted, though it is frequently ascribed to him. 27

Dr. Reginald Peacock, Bishop of Chichester, in his Repressor, written about 1449, combats "this opinioun, that a man which stale sumtyme a birthan of thornis was sett in to the moone, there for to abide for euere."

Thomas Dekker, a British dramatist, wrote in 1630: "A starre? Nay, thou art more than the moone, for thou hast neither changing quarters, nor a man standing in thy circle with a bush of thornes." 28

And last, but not least, amid the tuneful train, William Shakespeare, without whom no review of English literature or of poetic lore could be complete, twice mentions the man in the moon. First, in the Midsummer Night's Dream, Act iii. Scene 1, Quince the carpenter gives directions for the performance of Pyramus and Thisby, who "meet by moonlight," and says, "One must come in with a bush of thorns and a lanthorn, and say he comes to disfigure, or to present, the person of Moonshine." Then in Act v. the player of that part says, "All that I have to say is, to tell you that the lanthorn is the moon; I, the man in the moon; this thorn-bush, my thorn-bush; and this dog, my dog." And, secondly, in the Tempest, Act ii., Scene 2, Caliban and Stephano in dialogue:

Robert Chambers refers the following singular

lines to the man in the moon: adding, "The allusion to Jerusalem pipes is curious; Jerusalem is often applied, in Scottish popular fiction, to things of a nature above this world":

Here is an old-fashioned couplet belonging probably to our northern borders:

Halliwell explains sowins to be a Northumberland dish of coarse oatmeal and milk, and a cutty spoon to be a very small spoon. 30

Wales is not without a memorial of this myth, for Mr. Baring-Gould tells us that "there is an ancient pictorial representation of our friend the Sabbath-breaker in Gyffyn Church, near Conway. The roof of the chancel is divided into compartments, in four of which are the evangelistic symbols, rudely, yet effectively painted. Besides these symbols is delineated in each compartment an orb of heaven. The sun, the moon, and two stars, are placed at the feet of the Angel, the Bull, the Lion, and the Eagle. The representation of the moon is as follows: in the disk is the conventional man with his bundle of sticks, but without the dog." 31 Mr. Gould says, "our friend the Sabbath-breaker perhaps the artist

would have said "the thief," for stealing appears to be more antique.

A French superstition, lingering to the present day, regards the man in the moon as Judas Iscariot, transported to the moon for his treason. This plainly is a Christian invention. Some say the figure is Isaac bearing a burthen of wood for the sacrifice of himself on Mount Moriah. Others that it is Cain carrying a bundle of thorns on his shoulder, and offering to the Lord the cheapest gift from the field. 32 This was Dante's view, as the succeeding passages will show:

When we leave Europe, and look for the man in the moon under other skies, we find him, but with an altogether new aspect. He is the same, and yet another; another, yet the same. In China he plays a pleasing part in connubial affairs. "The Chinese 'Old Man in the Moon' is known as Yue-lao, and is reputed to hold in his hands the power of predestining the marriages of mortals--so that marriages, if not, according to the native idea, exactly made in heaven, are made somewhere beyond the bounds of earth. He is supposed to tie together the future husband and wife with an invisible silken cord, which never parts so long as life exists." 34 This must be the man of the Honey-moon, and we shall not meet his superior in any part of the world. Among the Khasias of the Himalaya Mountains "the changes of the moon are accounted for by the theory that this orb, who is a man, monthly falls in love with his wife's mother, who throws ashes in his face. The sun is female." 35 The Slavonic legend, following the Himalayan, says that "the moon, King of night and husband of the sun, faithlessly loves the morning Star, wherefore he was cloven through in punishment, as we see him in the sky." 36

This process is repeated until almost the whole of the moon is cut away, and only a little piece left; which the moon piteously implores the sun to spare for his (the moon's) children. (The moon is in Bushman mythology a male being.) From this little piece, the moon gradually grows again until it becomes a full moon, when the sun's stabbing and cutting processes recommence." 37

We cross the Atlantic, and among the Greenlanders discover a myth, which is sui generis. "The sun and moon are nothing else than two mortals, brother and sister. They were playing with others at children's games in the dark, when Malina, being teased in a shameful manner by her brother Anninga, smeared her hands with the soot of the lamp, and rubbed them over the face and hands of her persecutor, that she might recognise him by daylight. Hence arise the spots in the moon. Malina wished to save herself by flight, but her brother followed at her heels. At length she flew upwards, and became the sun. Anninga followed her, and became the moon; but being unable to mount so high, he runs continually round the sun, in hopes of some time surprising her. When he is tired and hungry in his last quarter, he leaves his house on a sledge harnessed to four huge dogs, to hunt seals, and continues abroad for several days. He now fattens so prodigiously on the spoils of the chase, that he soon grows into the full moon. He rejoices on the death of women, and the sun has her revenge on the death of men; all males therefore keep within doors during an eclipse of the sun, and females during that of the moon." 38This Esquimaux story, which has some interesting features, is told differently by Dr. Hayes, the Arctic explorer, who puts a lighted taper into the sun's hands, with which she discovered her brother, and which now causes her bright light, "while the moon, having lost his taper, is cold, and could not be seen but for his sister's light." 39 This belief prevails as far south as Panama, for the inhabitants of the Isthmus of Darien have a tradition that the man in the moon was guilty of gross misconduct towards his elder sister, the sun. 40

The Creek Indians say that the moon is inhabited by a man and a dog. The native tribes of British Columbia, too, have their myth. Mr. William Duncan writes to the Church Missionary Society: "One very dark night I was told that there was a moon to be seen on the beach. On going to see, there was an illuminated disk, with the figure of a man upon it. The water was then very low, and one of the conjuring parties had lit up this disk at the water's edge. They had made it to wax with great exactness, and presently it was at full. It was an imposing sight. Nothing could be seen around it; but the Indians suppose that the medicine party are then holding converse with the man in the moon." 41 Mr. Duncan was at another time led to the ancestral village of a tribe of Indians, whose chief said to him: "This is the place where our forefathers lived, and they told us something we want to tell you. The story is as follows: 'One night a child of the chief class awoke and cried for water. Its cries were very affecting--"Mother, give me to drink!" but the mother heeded not. The moon was affected, and came down, entered the house, and approached the child, saying, "Here is water from heaven: drink." The child anxiously laid hold of the pot and drank the draught, and was enticed to go away with the moon, its benefactor. They took an underground passage till they got quite clear of the village, and then ascended to heaven.' And," said the chief, "our forefathers tell us that the figure we now see in the moon is that very child; and also the little round basket which it had in its hand when it went to sleep appears there." 42

The aborigines of New Zealand have a suggestive version of this superstition. It is quoted from D'Urville by De Rougemont in his Le Peuple Primitif (tom. ii. p. 245), and is as follows:--"Before the moon gave light, a New Zealander named Rona went out in the night to fetch some water from the well. But he stumbled and unfortunately sprained his ankle, and was unable to return home. All at once, as he cried out for very anguish, he beheld with fear and horror that the moon, suddenly becoming visible, descended towards him. He seized hold of a tree, and clung to it for safety; but it gave way, and fell with Rona upon the moon; and he remains there to this day." 43 Another account of Rona varies in that he escapes falling into the well by seizing a tree, and both he and the tree were caught up to the moon. The variation indicates that the legend has a living root.

Here we terminate our somewhat wearisome wanderings about the world and through the mazes of mythology in quest of the man in the moon. As we do so, we are constrained to emphasize the striking similarity between the Scandinavian myth of Jack and Jill, that exquisite tradition of the British Columbian chief, and the New Zealand story of Rona. When three traditions, among peoples so far apart geographically, so essentially agree in one, the lessons to be learned from comparative mythology ought not to be lost upon the philosophical student of human history. To the believer in the unity of our race such a comparison of legends is of the greatest importance. As Mr. Tylor tells us, "The number of myths recorded as found in different countries, where it is hardly conceivable that they should have grown independently, goes on steadily increasing from year to year, each one furnishing a new clue by which common descent or intercourse is to be traced." 44 The same writer says on another page of his valuable work, "The mythmaking faculty belongs to mankind in general, and manifests itself in the most distant regions, where its unity of principle develops itself in endless variety of form." 45 Take, for example, China and England, representing two distinct races, two languages, two forms of religion, and two degrees of civilization yet, as W. F. Mayers remarks, "No one can compare the Chinese legend with the popular European belief in the 'Man in the Moon,' without feeling convinced of the certainty that the Chinese superstition and the English nursery tale are both derived from kindred parentage, and are linked in this relationship by numerous subsidiary ties. In all the range of Chinese mythology there is, perhaps, no stronger instance of identity with the traditions that have taken root in Europe than in the case of the legends relating to the moon." 46 This being the case, our present endeavour to establish the consanguinity of the nations, on the ground of agreement in myths and modes of faith and worship, cannot be labour thrown away. The recognition of friends in heaven is an interesting speculation; but far more good must result, as concerns this life at least, from directing our attention to the recognition of friends on earth. If we duly estimate the worth of any comparative science, whether of anatomy or philology, mythology or religion, this is the grand generalization to be attained, essential unity consistent and concurrent with endless multiformity; many structures, but one life; many creeds, but one faith; many beings and becomings, but all emanating from one Paternity, cohering through one Presence, and converging to one Perfection, in Him who is the Author and Former and Finisher of all things which exist. Let no man therefore ridicule a myth as puerile if it be an aid to belief in that commonweal of humanity for which the Founder of the purest religion was a witness and a martyr. We have sought out the man in the moon mainly because it was one out of many scattered stories which, as Max Müller nobly says, "though they may be pronounced childish and tedious by some critics, seem to me to glitter with the brightest dew of nature's own poetry, and to contain those very touches that make us feel akin, not only with Homer or Shakespeare, but even with Lapps, and Finns, and Kaffirs." 47 Vico discovered the value of myths, as an addition to our knowledge of the mental and moral life of the men of the myth-producing period. Professor Flint tells us that mythology, as viewed by the contemporaries of Vico, "appeared to be merely a rubbish-heap, composed of waste, worthless, and foul products of mind; but he perceived that it contained the materials for a science which would reflect the mind and history of humanity, and even asserted some general principles as to how these materials were to be interpreted and utilised, which have since been established, or at least endorsed, by Heyne, Creuzer, C O Müller, and others." 48 Let us cease to call that common which God has cleansed, and with thankfulness recognise the solidarity of the human race, to which testimony is borne by even a lunar myth.

We now return to the point whence we deflected, and rejoin the chief actor in the selenographic comedy. It is a relief to get away from the legendary man in the moon, and to have the real man once more in sight. We are like the little boy, whom the obliging visitor, anxious to show that he was passionately fond of children, and never annoyed by them in the least, treated to a ride upon his knee. "Trot, trot, trot; how do you enjoy that, my little man? Isn't that nice?" "Yes, sir," replied the child, "but not so nice as on the real donkey, the one with the four legs." It is true, the mythical character has redeeming traits; but then he breaks the Sabbath, obstructs people going to mass, steals cabbages, and is undergoing sentence of transportation for life. While the real man, who lives in a well-lighted crescent, thoroughly ventilated; whose noble profile is sometimes seen distinctly when he passes by on the shady side of the way; whose beaming countenance is at other times turned full upon us, reflecting nothing but sunshine as he winks at his many admirers: he is a being of quite another order. We do not forget that he has been represented with a claret jug in one hand, and a claret cup in the other; that he frequently takes half and half; that he is a smoker; that he sometimes gets up when other people are going to bed; that he often stops out all the night; and is too familiar with the low song--

"We won't go home till morning."

But these are mere eccentricities of greatness, and with all such irregularities he is "a very delectable, highly respectable" young fellow; in short,

Why, he has been known to take the shine out of old Sol himself; though from his partiality to us it always makes him look black in the face when we, Alexander-like, stand between him and that luminary. We, too, are the only people by whom he ever allows himself to be eclipsed. Illustrious man in the moon I he has lifted our thoughts from earth to heaven, and we are reluctant to leave him. But the best of friends must part; especially as other lunar inhabitants await attention.

"Other inhabitants!" some one may exclaim. Surely! we reply; and though it will necessitate a digression, we touch upon the question en passant. Cicero informs us that "Xenophanes says that the moon is inhabited, and a country having several towns and mountains in it." 49 This single dictum will be sufficient for those who bow to the influence of authority in matters of opinion. Settlement of questions by "texts" is a saving of endless pains. For that there are such lunar inhabitants must need little proof. Every astronomer is aware that the moon is full of craters; and every linguist is aware that "cratur" is the Irish word for creature. Or, to state the argument syllogistically, as our old friend Aristotle would have done: "Craturs" are inhabitants; the moon is full of craters; therefore the moon is full of inhabitants. We appeal to any unbiased mind whether such argumentation is not as sound as much of our modern reasoning, conducted with every pretence to logic and lucidity. Besides, who has not heard of that astounding publication, issued fifty years since, and entitled Great Astronomical Discoveries lately made by Sir John Herschel, LL.D., F.R.S., etc., at the Cape of Good Hope? One writer dares to designate it a singular satire; stigmatizes it as the once celebrated Moon Hoax, and attributes it to one Richard Alton Locke, of the United States. What an insinuation! that a man born under the star-spangled banner could trifle with astronomy. But if a few incredulous persons doubted, a larger number of the credulous believed. When the first number appeared in the New York Sun, in September, 1835, the excitement aroused was intense. The paper sold daily by thousands; and when the articles came out as a pamphlet, twenty thousand went off at once. Not only in Young America, but also in Old England, France, and throughout Europe, the wildest enthusiasm prevailed. Could anybody reasonably doubt that Sir John had seen wonders, when it was known that his telescope contained a prodigious lens, weighing nearly seven tons, and possessing a magnifying power estimated at 42,000 times? A reverend astronomer tells us that Sir Frederick Beaufort, having occasion to write to Sir John Herschel at the Cape, asked if he had heard of the report current in England that he (Sir John) had discovered sheep, oxen, and flying men in the moon. Sir John had heard the report; and had further heard that an American divine had "improved" the revelations. The said divine had told his congregation that, on account of the wonderful discoveries of the present age, lie lived in expectation of one day calling upon them for a subscription to buy Bibles for the benighted inhabitants of the moon. 50 What more needs to be said? Give our astronomical mechanicians a little time, and they will produce an instrument for full verification of these statements regarding the lunar inhabitants; and we may realize more than we have imagined or dreamed. We may obtain observations as satisfactory as those of a son of the Emerald Isle, who was one day boasting to a friend of his excellent telescope. "Do you see yonder church?" said he. "Although it is scarcely discernible with the naked eye, when I look at it through my telescope, it brings it so close that I can hear the organ playing." Two hundred years ago, a wise man witnessed a wonderful phenomenon in the moon: he actually beheld a live elephant there. But the unbelieving have ever since made all manner of fun at the good knight's expense. Take the following burlesque of this celebrated discovery as an instance. "Sir Paul Neal, a conceited virtuoso of the seventeenth century, gave out that he had discovered 'an elephant in the moon.' It turned out that a mouse had crept into his telescope, which had been mistaken for an elephant in the moon." 51 Well, we concede that an elephant and a mouse are very much alike; but surely Sir Paul was too sagacious to be deceived by resemblances. If we had more faith, which is indispensable in such matters, the revelations of science, however extraordinary or extravagant, would be received without a murmur of distrust. We should not then meet with such sarcasm as we found in the seventeenth century Jest Bookbefore quoted: "One asked why men should thinke there was a world in the moone? It was answered, because they were lunatique."

According to promise, we must make mention of at least one visit paid by our hero to this lower world. We do this in the classic language of a student of that grand old University which stands in the city of Oxford. May the horns of Oxford be exalted, and the shadow of the University never grow less, while the moon endureth!

Poor man in the moon! what a way he must have been in! We hope that he found improving fellowship, say among the Fellows of some Royal Astronomical Society; and that when he returned to his skylight, or lighthouse on the coast of immensity's wide sea, he returned a wiser and much happier man. It is for us, too, to remember with Spenser, "The noblest mind the best contentment has."

And now we record a few visits which men of this sublunary sphere are said to have paid to the moon. The chronicles are unfortunately very incomplete. Aiming at historical fulness and fidelity, we turned to our national bibliotheca at the British Museum, where we fished out of the vasty deep of treasures a MS. without date or name. We wish the Irish orator's advice were oftener followed by literary authors. Said he, "Never write an anonymous letter without signing your name to it." This MS. is entitled "Selenographia, or News from the world in the moon to the lunatics of this world. By Lucas Lunanimus of Lunenberge." 53 We are here told how the author, "making himself a kite of ye hight(?) of a large sheet, and tying himself to the tayle of it, by the help of some trusty friends, to whom he promised mountains of land in this his new-found world; being furnished also with a tube, horoscope, and other instruments of discovery, he set saile the first of Aprill, a day alwaies esteemed prosperous for such adventures." Fearing, however, lest the date of departure should make some suspicious that the author was desirous of making his readers April fools, we leave this aërial tourist to pursue his explorations without our company, and listen to a learned bishop, who ought to be a canonical authority, for the man in the moon himself is an overseer of men. Dr. Francis Godwin, first of Llandaff, afterwards of Hereford, wrote about the year 1600 The Man in the Moone, or a discourse of a voyage thither. This was published in 1638, under the pseudonym of Domingo Gonsales. The enterprising aeronaut went up from the island of El Pico, carried by wild swans. Swans, be it observed. It was not a wild-goose chase. The author is careful to tell us what we believe so soon as it is declared. "The further we went, the lesser the globe of the earth appeared to us; whereas still on the contrary side the moone showed herselfe more and more monstrously huge." After eleven days' passage, the exact time that Arago allowed for a cannon ball to reach the moon, "another earth" was approached. "I perceived that it was covered for the most part with a huge and mighty sea, those parts only being drie land, which show unto us here somewhat darker than the rest of her body; that I mean which the country people call el hombre della Luna, the man of the moone."

[paragraph continues]This last clause demands a protest. The bishop knocks the country-people's man out of the moon, to make room for his own man, which episcopal creation is twenty-eight feet high, and weighs twenty-five or thirty of any of us. Besides ordinary men, of extraordinary measurement, the bishop finds in the moon princes and queens. The females, or lunar ladies, as a matter of course, are of absolute beauty. Their language has "no affinity with any other I ever heard." This is a poor look-out for the American divine who expects to send English Bibles to the moon. "Food groweth everywhere without labour": this is a cheering prospect for our working classes who may some day go there. "They need no lawyers": oh what a country! "And as little need is there of physicians." Why, the moon must be Paradise regained. But, alas! "they die, or rather (I should say) cease to live." Well, my lord bishop, is not that how we die on earth? Perhaps we need to be learned bishops to appreciate the difference. If so, we might accept episcopal distinction.

Lucian, the Greek satirist, in his Voyage to the Globe of the Moon, sailed through the sky for the space of seven days and nights and on the eighth "arrived in a great round and shining island which hung in the air and yet was inhabited. These inhabitants were Hippogypians, and their king was Endymion." 54 Some of the ancients thought the lunarians were fifteen times larger than we are, and our oaks but bushes compared with their trees. So natural is it to magnify prophets not of our own country.

William Hone tells us that a Mr. Wilson, formerly curate of Halton Gill, near Skipton-in-Craven, Yorkshire, in the last century wrote a tract entitled The Man in the Moon, which was seriously meant to convey the knowledge of common astronomy in the following strange vehicle: A cobbler, Israel Jobson by name, is supposed to ascend first to the top of Penniguit; and thence, as a second stage equally practicable, to the moon; after which he makes the grand tour of the whole solar system. From this excursion, however, the traveller brings back little information which might not have been had upon earth, excepting that the inhabitants of one of the planets, I forget which, were made of "pot metal." 55 This curious tract, full of other extravagances, is rarely if ever met with, it having been zealously bought up by its writer's family.

We must not be detained with any detailed account of M. Jules Verne's captivating books, entitled From the Earth to the Moon, and Around the Moon. They are accessible to all, at a trifling cost. Besides, they reveal nothing new relating to the Hamlet of our present play. Nor need we more than mention "the surprising adventures of the renowned Baron Munchausen." His lunarians being over thirty-six feet high, and "a common flea being much larger than one of our sheep," 56 Munchausen's moon must be declined, with thanks.

"Certain travellers, like the author of the Voyage au monde de Descartes, have found, on visiting these different lunar countries, that the great men whose names they had arbitrarily received took possession of them in the course of the sixteenth century, and there fixed their residence. These immortal souls, it seems, continued their works and systems inaugurated on earth. Thus it is, that on Mount Aristotle a real Greek city has risen, peopled with peripatetic philosophers, and guarded by sentinels armed with propositions, antitheses, and sophisms, the master himself living in the centre of the town in a magnificent palace. Thus also in Plato's circle live souls continually occupied in the study of the prototype of ideas. Two years ago a fresh division of lunar property was made, some astronomers being generously enriched." 57

That the moon is an abode of the departed spirits of men, an upper hades, has been believed for ages. In the Egyptian Book of Respirations, which M. p. J. de Horrack has translated from the MS. in the Louvre in Paris, Isis breathes the wish for her brother Osiris "that his soul may rise to heaven in the disk of the moon." 58 Plutarch says, "Of these soules the moon is the element, because soules doe resolve into her, like as the bodies of the dead into the earth." 59 To this ancient theory Mr. Tylor refers when he writes, "And when in South America the Saliva Indians have pointed out the moon, their paradise where no mosquitoes are, and the Guaycurus have shown it as the home of chiefs and medicine-men deceased, and the Polynesians of Tokelau in like manner have claimed it as the abode of departed kings and chiefs, then these pleasant fancies may be compared with that ancient theory mentioned by Plutarch, that hell is in the air and elysium in the moon, and again with the mediæval conception of the moon as the seat of hell, a thought elaborated in profoundest bathos by Mr. M. F. Tupper:

Skin for skin, the brown savage is not ill-matched in such speculative lore with the white philosopher." 60

The last journey to the moon on our list we introduce for the sake of its sacred lesson. Pure religion is an Attic salt, which wise men use in all of their entertainments: a condiment which seasons what is otherwise insipid, and assists healthy digestion in the compound organism of man's mental and moral constitution. About seventy years since, a little tract was published, in which the writer imagined himself on luna firma. After giving the inhabitants of the moon an account of our terrestrial race, of its fall and redemption, and of the unhappiness of those who neglect the great salvation, he says, "The secret is this, that nothing but an infinite God, revealing Himself by His Spirit to their minds, and enabling them to believe and trust in Him, can give perfect and lasting satisfaction." He then adds, "My last observation received the most marked approbation of the lunar inhabitants: they truly pitied the ignorant triflers of our sinful world, who prefer drunkenness, debauchery, sinful amusements, exorbitant riches, flattery, and other things that are highly esteemed amongst men, to the pleasures of godliness, to the life of God in the soul of man, to the animating hope of future bliss." 61

Here the man in the moon and we must part. Hitherto some may have supposed their thoughts occupied with a mere creature of imagination, or gratuitous creation of an old-world mythology. Perhaps the man in the moon is nothing more: perhaps he is very much more. Possibly we have information of every being in the universe; and possibly there are beings in every existing world of which we know nothing whatever. The latter possibility we deem much the more probable. Remembering our littleness as contrasted with the magnitude of the whole creation, we prefer to believe that there are rational creatures in other worlds besides this small-sized sphere in, it may be, a small-sized system. Therefore, till we acquire more conclusive evidence than has yet been adduced, we will not regard even the moon as an empty abode, but as the home of beings

whom, in the absence of accurate definition, we denominate men. Whether the man in the moon have a body like our own, whether his breathing apparatus, his digestive functions, and his cerebral organs, be identical with ours, are matters of secondary moment. The Fabricator of terrestrial organizations has limited himself to no one type or form, why then should man be the model of beings in distant worlds? Be the man in the moon a biped or quadruped; see he through two eyes as we do, or a hundred like Argus; hold he with two hands as we do, or a hundred like Briarius; walk he with two feet as we do, or a hundred like the centipede, "the mind's the standard of the man" everywhere. If he have but a wise head and a warm heart; if he be not shut up, Diogenes--like, within his own little tub of a world, but take an interest in the inhabitants of kindred spheres; and if he be a worshipper of the one God who made the heavens with all their glittering hosts;--then, in the highest sense, he is a man, to whom we would fain extend the hand of fellowship, claiming him as a brother in that universal family which is confined to no bone or blood, no colour or creed, and, so far as we can conjecture, to no world, but is co-extensive with the household of the Infinite Father, who cares for all of His children, and will ultimately blend them in the blessed bonds of an endless confraternity. Whether we or our posterity will ever become better acquainted in this life with the man in the moon is problematical; but in the ages to come, "when the

manifold wisdom of God" shall be developed among "the principalities and powers in heavenly places," he may be something more than a myth or topic of amusement. He may be visible among the first who will declare every man in his own tongue wherein he was born the wonderful works of God, and he may be audible among the first who will lift their hallelujahs of undivided praise when every satellite shall be a chorister to laud the universal King. Let us, brothers of earth, by high and holy living, learn the music of eternity; and then, when the discord of "life's little day " is hushed, and we are called to join in the everlasting song, we may solve in one beatific moment the problem of the plurality of worlds, and in that solution we shall see more than we have been able to see at present of the man in the moon.

MOON INHABITATION.

SCIENCE having practically diminished the moon's distance, and rendered distinct its elevations and depressions, it is natural for " those obstinate questionings of sense and outward things " to urge the inquiry, Is the moon inhabited? This question it is easier to ask than to answer. It has been a mooted point for many years, and our wise men of the west seem still disposed to give it up, or, at least, to adjourn its decision for want of evidence. Of "guesses at truth" there have been a great multitude, and of dogmatic assertions not a few; but demonstrations are things which do not yet appear. We now take leave to report progress, and give the subject a little ventilation. We do not expect to furnish an Ariadne's thread, but we may hope to find some indication of the right way out of this labyrinth of uncertainty. Veritas nihil veretur nisi abscondi: or, as the German proverb says, "Truth creeps not into corners"; its life is the light.

But before we advance a single step, we desire to preclude all misunderstanding on one point, by distinctly avowing our conviction that the teachings of Christian theology are not at all involved in the issue of this discussion, whatever it may prove. Infinite harm has been done by confusing the religion of science with the science of religion. Religion is a science, and science is a religion; but they are not identical. Philosophy ought to be pious, and piety ought to be philosophical; but philosophy and piety are two quantities and qualities that may dwell apart, though, happily, they may also be found in one nature. Each has its own faculties and functions; and in our present investigation, religion has nothing more to do than to shed the influence of reverence, humility, and teachableness over the scientific student as he ponders his problem and works out the truth. In this, and in kindred studies, we may yield without reluctance what a certain professor of religion concedes, and grant without grudging what a certain professor of science demands. Dr. James Martineau says, "In so far as Church belief is still committed to a given kosmogony and natural history of man, it lies open to scientific refutation"; and again, "The whole history of the Genesis of things Religion must unconditionally surrender to the Sciences." 421 In this we willingly concur, for science ought to be, and will be, supreme in its own domain. Bishop Temple does "not hesitate to ascribe to Science a clearer knowledge of the true interpretation of the first chapter of Genesis, and to scientific history a truer knowledge of the great historical prophets. Science enters into Religion, and the believer is bound to recognise its value and make use of its services." 422 Then, to quote the professor of science, Dr. John Tyndall says. "The impregnable position of science may be described in a few words. We claim, and we shall wrest from Theology, the entire domain of cosmological theory." 423 We wish the eloquent professor all success. It was not the spirit of primitive Christianity, but the spirit of priestly ignorance, intolerance, and despotism, which invaded the territory of natural science; and if those who are its rightful lords can recover the soil, we bid them heartily, God speed! We have been driven to these remarks by a twofold impulse. First, we can never forget the injury that has been inflicted on science by the oppositions of a headless religion; any more than we can forget the injury which has been inflicted on religion by the oppositions of a heartless science. Secondly, we have seen this very question of the inhabitation of the planets and satellites rendered a topic of ridicule for Thomas Paine, and an inviting theme for raillery to others of sophistical spirit, by the way in which it has been foolishly mixed up with sacred or spiritual concerns. Surely, the object of God in the creation of our terrestrial race, or the benefits of the death of Jesus Christ, can have no more to do with the habitability of the moon, than the doctrine of the Trinity has to do with the multiplication table and the rule of three, or

the hypostatical union with the chemical composition of water and light. Having said thus much of compulsion, we return, not as ministers in the temple of religion so much as students in the school of science, to consider with docility the question in dispute, Is the moon inhabited?

Three avenues, more or less umbrageous, are open to us; all of which have been entered. They may be named observation, induction, and analogy. The first, if we could pursue it, would explicate the enigma at once. The second, if clear, would satisfy our reason, which, in such a matter, might be equivalent to sight. And the third might conduct us to a shadow which would "prove the substance true." We begin by dealing briefly with the argument from observation. Here our data are small and our difficulties great. One considerable inconvenience in the inquiry is, of course, the moon's distance. Though she is our next-door neighbour in the many-mansioned universe, two hundred and thirty-seven thousand miles are no mere step heavenward. Transit across the intervenient space being at present impracticable, we have to derive our most enlarged views of this "spotty globe" from the "optic glass." But this admirable appliance, much as it has revealed, is thus far wholly inadequate to the solution of our mystery. Robert Hooke, in the seventeenth century, thought that he could construct a telescope with which we might discern the inhabitants of the moon life-size-seeing them as

plainly as we see the inhabitants of the earth. But, alas! the sanguine mathematician died in his sleep, and his dream has not yet come true. Since Hooke's day gigantic instruments have been fitted up, furnished with all the modern improvements which could be supplied through the genius or generosity of such astronomers as Joseph Fraunhofer and Sir William Herschel, the third Earl of Rosse and the fourth Duke of Northumberland. But all of these worthy men left something to be done by their successors. Consequently, not long since, our scientists set to work to increase their artificial eyesight. The Rev. Mr. Webb tells us that "the first 'Moon Committee' of the British Association recommended a power of 1,000." But he discourages us if we anticipate large returns; for he adds: "Few indeed are the instruments or the nights that will bear it; but when employed, what will be the result? Since increase of magnifying is equivalent to decrease of distance, we shall see the moon as large (though not as distinct) as if it were 240 miles off, and any one can judge what could be made of the grandest building upon earth at that distance." 424 If therefore we are to see the settlement of the matter in the speculum of a telescope, it may be some time before we have done with what Guillemin calls "the interesting, almost insoluble question, of the existence of living and organized beings on the surface of the satellite of our little earth." 425 Some cynic may interpose with the quotation,--

"But optics sharp it needs, I ween,

To see what is not to be seen." 426

True, but it remains to be shown that there is nothing to be seen beyond what we see. We are not prepared to deny the existence of everything which our mortal eyes may fail to trace. Four hundred years ago all Europe believed that to sail in search of a western continent was to wish "to see what is not to be seen"; but a certain Christopher Columbus went out persuaded of things not seen as yet, and having embarked in faith he landed in sight. The lesson must not be lost upon us.

"There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy."

Because we cannot now make out either habitations or habitants on the moon, it does not necessarily follow that the night will never come when, through some mightier medium than any ever yet constructed or conceived, we shall descry, beside mountains and valleys, also peopled plains and populous cities animating the fair features of this beautiful orb. One valuable auxiliary of the telescope, destined to play an important part in lunar discovery, must not be overlooked. Mr. Norman Lockyer says, "With reference to the moon, if we wish to map her correctly, it is now no longer necessary to depend on ordinary eye observations alone; it is perfectly clear that by means of an image of the moon, taken by photography, we are able to fix many points on the lunar surface." 427[paragraph continues]

With telescopic and photographic lenses in skilled hands, and a wealth of inventive genius in fertile brains, we can afford to wait a long while before we close the debate with a final negative.

In the meantime, eyes and glasses giving us no satisfaction, we turn to scientific induction. Speculation is a kind of mental mirror, that before now has anticipated or supplemented the visions of sense. Not being practical astronomers ourselves, we have to follow the counsel of that unknown authority who bids us believe the expert. But expertness being the fruit of experience, we may be puzzled to tell who have attained that rank. We will inquire, however, with due docility, of the oracles of scientific research. It is agreed on all sides that to render the moon habitable by beings at all akin with our own kind, there must be within or upon that body an atmosphere, water, changing seasons, and the alternations of day and night. We know that changes occur in the moon, from cold to heat, and from darkness to light. But the lunar day is as long as 291 of ours; so that each portion of the surface is exposed to, or turned from, the sun for nearly 14 days. This long exposure produces excessive heat, and the long darkness excessive cold. Such extremities of temperature are unfavourable to the existence of beings at all like those living upon the earth, especially if the moon be without water and atmosphere. As these two desiderata seem indispensable to lunar inhabitation, we may chiefly consider the question, Do these conditions

exist? If so, inductive reasoning will lead us to the inference, which subsequent experience will strengthen, that the moon is inhabited like its superior planet. But if not, life on the satellite similar to life on the earth, is altogether improbable, if not absolutely impossible.

The replies given to this query will be by no means unanimous. But, for the full understanding of the state of the main question, and to assist us in arriving at some sort of verdict, we will hear several authorities on both sides of the case. The evidence being cumulative, we pursue the chronological order, and begin with La Place. He writes: "The lunar atmosphere, if any such exists, is of an extreme rarity, greater even than that which can be produced on the surface of the earth by the best constructed air-pumps. It may be inferred from this that no terrestrial animal could live or respire at the surface of the moon, and that if the moon be inhabited, it must be by animals of another species." 428 This opinion, as Sir David Brewster points out, is not that the moon has no atmosphere, but that if it have any it is extremely attenuated. Mr. Russell Hind's opinion is similar with respect to water. He says: "Earlier selenographists considered the dull, grayish spots to be water, and termed them the lunar seas, bays, and lakes. They arc so called to the present day, though we have strong evidence to show that if water exist at all on the moon, it must be in very small quantity." 429 Mr. Grant tells us that "the

question whether the moon be surrounded by an atmosphere has been much discussed by astronomers. Various phenomena are capable of indicating such an atmosphere, but, generally speaking, they are found to be unfavourable to its existence, or at all events they lead to the conclusion that it must be very inconsiderable." 430 Humboldt thinks that Schroeter's assumptions of a lunar atmosphere and lunar twilight are refuted, and adds: "If, then, the moon is without any gaseous envelope, the entire absence of any diffused light must cause the heavenly bodies, as seen from thence, to appear projected against a sky almost black in the day-time. No undulation of air can there convey sound, song, or speech. The moon, to our imagination, which loves to soar into regions inaccessible to full research, is a desert where silence reigns unbroken." 431 Dr. Lardner considers it proven "that there does not exist upon the moon an atmosphere capable of reflecting light in any sensible degree," and also believes that "the same physical tests which show the non-existence of an atmosphere of air upon the moon are equally conclusive against an atmosphere of vapour." 432 Mr. Breen is more emphatic. He writes: "In the want of water and air, the question as to whether this body is inhabited is no longer equivocal. Its surface resolves itself into a sterile and inhospitable waste, where the lichen which flourishes amidst the frosts and snows of Lapland would quickly wither and die, and where no animal with a drop of blood in its veins could exist." 433 The anonymous

author of the Essay on the Plurality of Worlds announces that astronomers are agreed to negative our question without dissent. We shall have to manifest his mistake. His words are: "Now this minute examination of the moon's surface being possible, and having been made by many careful and skilful astronomers, what is the conviction which has been conveyed to their minds with regard to the fact of her being the seat of vegetable or animal life? Without exception, it would seem, they have all been led to the belief that the moon is not inhabited; that she is, so far as life and organization are concerned, waste and barren, like the streams of lava or of volcanic ashes on the earth, before any vestige of vegetation has been impressed upon them; or like the sands of Africa, where no blade of grass finds root." 434Robert Chambers says: "It does not appear that our satellite is provided with an atmosphere of the kind found upon earth; neither is there any appearance of water upon the surface. . . . These characteristics of the moon forbid the idea that it can be at present a theatre of life like the earth, and almost seem to declare that it never can become so." 435 Schoedler's opinion is concurrent with what has preceded. He writes: "According to the most exact observations it appears that the moon has no atmosphere similar to ours, that on its surface there are no great bodies of water like our seas and oceans, so that the existence of water is doubtful. The whole physical condition of the lunar surface must, therefore, be so different

from that of our earth, that beings organized as we are could not exist there." 436 Another German author says: "The observations of Fraunhofer (1823), Brewster and Gladstone (1860), Huggins and Miller, as well as Janssen, agree in establishing the complete accordance of the lunar spectrum with that of the sun. In all the various portions of the moon's disk brought under observation, no difference could be perceived in the dark lines of the spectrum, either in respect of their number or relative intensity. From this entire absence of any special absorption lines, it must be concluded that there is no atmosphere in the moon, a conclusion previously arrived at from the circumstance that during an occultation no refraction is perceived on the moon's limb when a star disappears behind the disk." 437 Mr. Nasmyth follows in the same strain. Holding that the moon lacks air, moisture, and temperature, he says, "Taking all these adverse conditions into consideration, we are in every respect justified in concluding that there is no possibility of animal or vegetable life existing on the moon, and that our satellite must therefore be regarded as a barren world." 438 A French astronomer holds a like opinion, saying: "There is nothing to show that the moon possesses an atmosphere; and if there was one, it would be perceptible during the occultations of the stars and the eclipses of the sun. It seems impossible that, in the complete absence of air, the moon can be peopled by beings organized like ourselves, nor is there any sign of vegetation or

of any alteration in the state of its surface which can be attributed to a change of seasons." 439 On the same side Mr. Crampton writes most decisively, "With what we do know, however, of our satellite, I think the idea of her being inhabited may be dismissed summarily; i.e. her inhabitation by intelligent beings, or an animal creation such as exist here." 440 And, finally, in one of Maunder's excellent Treasuries, we read of the moon, "She has no atmosphere, or at least none of sufficient density to refract the rays of light as they pass through it, and hence there is no water on her surface; consequently she can have no animals like those on our planet, no vegetation, nor any change of seasons." 441These opinions, recorded by so many judges of approved ability and learning, have great weight; and some may regard their premisses and conclusions as irresistibly cogent and convincing. The case against inhabitation is certainly strong. But justice is impartial. Audi alteram partem.

Judges of equal erudition will now speak as respondents. We go back to the seventeenth century, and begin with a work whose reasoning is really remarkable, seeing that it is nearly two hundred and fifty years since it was first published. We refer to the Discovery of a New World by John Wilkins, Bishop of Chester; in which the reverend philosopher aims to prove the following propositions:--"1. That the strangeness of this opinion (that the moon may be a world) is no sufficient reason why it should be rejected; because

other certain truths have been formerly esteemed as ridiculous, and great absurdities entertained by common consent. 2. That a plurality of worlds does not contradict any principle of reason or faith. 3. That the heavens do not consist of any such pure matter which can privilege them from the like change and corruption, as these inferior bodies are liable unto. 4. That the moon is a solid, compacted, opacous body. 5. That the moon hath not any light of her own. 6. That there is a world in the moon, hath been the direct opinion of many ancient, with some modern mathematicians; and may probably be deduced from the tenets of others. 9. That there are high mountains, deep valleys, and spacious plains in the body of the moon. 10. That there is an atmosphœra, or an orb of gross vaporous air, immediately encompassing the body of the moon. 13. That 'tis probable there may be inhabitants in this other world; but of what kind they are, is uncertain." 442 We go on to 1686, and listen to the French philosopher, Fontenelle, in his Conversations with the Marchioness. "'Well, madam,' said I, 'you will not be surprised when you hear that the moon is an earth too, and that she is inhabited as ours is.' 'I confess,' said she, 'I have often heard talk of the world in the moon, but I always looked upon it as visionary and mere fancy.' 'And it may be so still,' said I. 'I am in this case as people in a civil war, where the uncertainty of what may happen makes them hold intelligence with the opposite party; for though I verily

believe the moon is inhabited, I live civilly with those who do not believe it; and I am still ready to embrace the prevailing opinion. But till the unbelievers have a more considerable advantage, I am for the people in the moon.'" 443 Whatever may be thought of his philosophy, no one could quarrel with the Secretary of the Academy on the score of his politeness or his prudence. A more recent and more reliable authority appears in Sir David Brewster. He tells us that "MM. Mädler and Beer, who have studied the moon's surface more diligently than any of their predecessors or contemporaries, have arrived at the conclusion that she has an atmosphere." Sir David himself maintains that "every planet and satellite in the solar system must have an atmosphere." 444 Bonnycastle, whilom professor of mathematics in the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, writes: "Astronomers were formerly of opinion that the moon had no atmosphere, on account of her never being obscured by clouds or vapours; and because the fixed stars, at the time of an occultation, disappear behind her instantaneously, without any gradual diminution of their light. But if we consider the effects of her days and nights, which are near thirty times as long as with us, it may be readily conceived that the phenomena of vapours and meteors must be very different. And besides, the vaporous or obscure part of our atmosphere is only about the one thousand nine hundred and eightieth part of the earth's diameter, as is evident from observing the clouds, which