Wednesday, 30 September 2020

HUNT

Tuesday, 29 September 2020

Nearer to God

The Remains of The Day

In my philosophy, Mr. Benn, a man cannot call himself well-contented until he has done all he can to be of service to his employer. Of course, this assumes that one's employer is a superior person, not only in rank, or wealth, but in moral stature.

LOVING SERVANT

DUKAT

SAINTS

Independence Day

The Signal-Man

THE SIGNAL-MAN. [312]

“Halloa! Below there!”

When he heard a voice thus calling to him, he was standing at the door of his box, with a flag in his hand, furled round its short pole. One would have thought, considering the nature of the ground, that he could not have doubted from what quarter the voice came; but instead of looking up to where I stood on the top of the steep cutting nearly over his head, he turned himself about, and looked down the Line. There was something remarkable in his manner of doing so, though I could not have said for my life what. But I know it was remarkable enough to attract my notice, even though his figure was foreshortened and shadowed, down in the deep trench, and mine was high above him, so steeped in the glow of an angry sunset, that I had shaded my eyes with my hand before I saw him at all.

“Halloa! Below!”

From looking down the Line, he turned himself about again, and, raising his eyes, saw my figure high above him.

“Is there any path by which I can come down and speak to you?”

He looked up at me without replying, and I looked down at him without pressing him too soon with a repetition of my idle question. Just then there came a vague vibration in the earth and air, quickly changing into a violent pulsation, and an oncoming rush that caused me to start back, as though it had force to draw me down. When such vapour as rose to my height from this rapid train had passed me, and was skimming away over the landscape, I looked down again, and saw him refurling the flag he had shown while the train went by.

I repeated my inquiry. After a pause, during which he seemed to regard me with fixed attention, he motioned with his rolled-up flag towards a point on my level, some two or three hundred yards distant. I called down to him, “All right!” and made for that point. There, by dint of looking closely about me, I found a rough zigzag descending path notched out, which I followed.

The cutting was extremely deep, and unusually precipitate. It was made through a clammy stone, that became oozier and wetter as I went down. For these reasons, I found the way long enough to give me time to recall a singular air of reluctance or compulsion with which he had pointed out the path.

When I came down low enough upon the zigzag descent to see him again, I saw that he was standing between the rails on the way by p. 313which the train had lately passed, in an attitude as if he were waiting for me to appear. He had his left hand at his chin, and that left elbow rested on his right hand, crossed over his breast. His attitude was one of such expectation and watchfulness that I stopped a moment, wondering at it.

I resumed my downward way, and stepping out upon the level of the railroad, and drawing nearer to him, saw that he was a dark, sallow man, with a dark beard and rather heavy eyebrows. His post was in as solitary and dismal a place as ever I saw. On either side, a dripping-wet wall of jagged stone, excluding all view but a strip of sky; the perspective one way only a crooked prolongation of this great dungeon; the shorter perspective in the other direction terminating in a gloomy red light, and the gloomier entrance to a black tunnel, in whose massive architecture there was a barbarous, depressing, and forbidding air. So little sunlight ever found its way to this spot, that it had an earthy, deadly smell; and so much cold wind rushed through it, that it struck chill to me, as if I had left the natural world.

Before he stirred, I was near enough to him to have touched him. Not even then removing his eyes from mine, he stepped back one step, and lifted his hand.

This was a lonesome post to occupy (I said), and it had riveted my attention when I looked down from up yonder. A visitor was a rarity, I should suppose; not an unwelcome rarity, I hoped? In me, he merely saw a man who had been shut up within narrow limits all his life, and who, being at last set free, had a newly-awakened interest in these great works. To such purpose I spoke to him; but I am far from sure of the terms I used; for, besides that I am not happy in opening any conversation, there was something in the man that daunted me.

He directed a most curious look towards the red light near the tunnel’s mouth, and looked all about it, as if something were missing from it, and then looked at me.

That light was part of his charge? Was it not?

He answered in a low voice,—“Don’t you know it is?”

The monstrous thought came into my mind, as I perused the fixed eyes and the saturnine face, that this was a spirit, not a man. I have speculated since, whether there may have been infection in his mind.

In my turn, I stepped back. But in making the action, I detected in his eyes some latent fear of me. This put the monstrous thought to flight.

“You look at me,” I said, forcing a smile, “as if you had a dread of me.”

“I was doubtful,” he returned, “whether I had seen you before.”

“Where?”

He pointed to the red light he had looked at.

Intently watchful of me, he replied (but without sound), “Yes.”

“My good fellow, what should I do there? However, be that as it may, I never was there, you may swear.”

“I think I may,” he rejoined. “Yes; I am sure I may.”

His manner cleared, like my own. He replied to my remarks with readiness, and in well-chosen words. Had he much to do there? Yes; that was to say, he had enough responsibility to bear; but exactness and watchfulness were what was required of him, and of actual work—manual labour—he had next to none. To change that signal, to trim those lights, and to turn this iron handle now and then, was all he had to do under that head. Regarding those many long and lonely hours of which I seemed to make so much, he could only say that the routine of his life had shaped itself into that form, and he had grown used to it. He had taught himself a language down here,—if only to know it by sight, and to have formed his own crude ideas of its pronunciation, could be called learning it. He had also worked at fractions and decimals, and tried a little algebra; but he was, and had been as a boy, a poor hand at figures. Was it necessary for him when on duty always to remain in that channel of damp air, and could he never rise into the sunshine from between those high stone walls? Why, that depended upon times and circumstances. Under some conditions there would be less upon the Line than under others, and the same held good as to certain hours of the day and night. In bright weather, he did choose occasions for getting a little above these lower shadows; but, being at all times liable to be called by his electric bell, and at such times listening for it with redoubled anxiety, the relief was less than I would suppose.

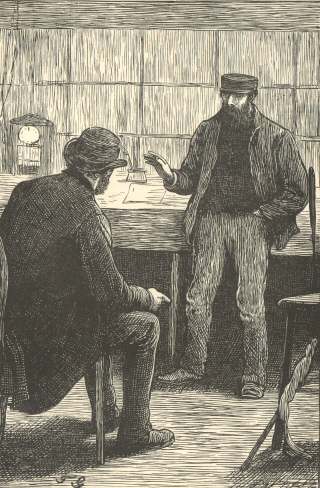

He took me into his box, where there was a fire, a desk for an official book in which he had to make certain entries, a telegraphic instrument with its dial, face, and needles, and the little bell of which he had spoken. On my trusting that he would excuse the remark that he had been well educated, and (I hoped I might say without offence) perhaps educated above that station, he observed that instances of slight incongruity in such wise would rarely be found wanting among large bodies of men; that he had heard it was so in workhouses, in the police force, even in that last desperate resource, the army; and that he knew it was so, more or less, in any great railway staff. He had been, when young (if I could believe it, sitting in that hut,—he scarcely could), a student of natural philosophy, and had attended lectures; but he had run wild, misused his opportunities, gone down, and never risen again. He had no complaint to offer about that. He had made his bed, and he lay upon it. It was far too late to make another.

All that I have here condensed he said in a quiet manner, with his grave, dark regards divided between me and the fire. He threw in the word, “Sir,” from time to time, and especially when he referred p. 315to his youth,—as though to request me to understand that he claimed to be nothing but what I found him. He was several times interrupted by the little bell, and had to read off messages, and send replies. Once he had to stand without the door, and display a flag as a train passed, and make some verbal communication to the driver. In the discharge of his duties, I observed him to be remarkably exact and vigilant, breaking off his discourse at a syllable, and remaining silent until what he had to do was done.

In a word, I should have set this man down as one of the safest of men to be employed in that capacity, but for the circumstance that while he was speaking to me he twice broke off with a fallen colour, turned his face towards the little bell when it did NOT ring, opened the door of the hut (which was kept shut to exclude the unhealthy damp), and looked out towards the red light near the mouth of the tunnel. On both of those occasions, he came back to the fire with the inexplicable air upon him which I had remarked, without being able to define, when we were so far asunder.

Said I, when I rose to leave him, “You almost make me think that I have met with a contented man.”

(I am afraid I must acknowledge that I said it to lead him on.)

“I believe I used to be so,” he rejoined, in the low voice in which he had first spoken; “but I am troubled, sir, I am troubled.”

He would have recalled the words if he could. He had said them, however, and I took them up quickly.

“With what? What is your trouble?”

“It is very difficult to impart, sir. It is very, very difficult to speak of. If ever you make me another visit, I will try to tell you.”

“But I expressly intend to make you another visit. Say, when shall it be?”

“I go off early in the morning, and I shall be on again at ten to-morrow night, sir.”

“I will come at eleven.”

He thanked me, and went out at the door with me. “I’ll show my white light, sir,” he said, in his peculiar low voice, “till you have found the way up. When you have found it, don’t call out! And when you are at the top, don’t call out!”

His manner seemed to make the place strike colder to me, but I said no more than, “Very well.”

“And when you come down to-morrow night, don’t call out! Let me ask you a parting question. What made you cry, ‘Halloa! Below there!’ to-night?”

“Heaven knows,” said I. “I cried something to that effect—”

“Not to that effect, sir. Those were the very words. I know them well.”

“Admit those were the very words. I said them, no doubt, because I saw you below.”

“What other reason could I possibly have?”

“You had no feeling that they were conveyed to you in any supernatural way?”

“No.”

He wished me good-night, and held up his light. I walked by the side of the down Line of rails (with a very disagreeable sensation of a train coming behind me) until I found the path. It was easier to mount than to descend, and I got back to my inn without any adventure.

Punctual to my appointment, I placed my foot on the first notch of the zigzag next night, as the distant clocks were striking eleven. He was waiting for me at the bottom, with his white light on. “I have not called out,” I said, when we came close together; “may I speak now?” “By all means, sir.” “Good-night, then, and here’s my hand.” “Good-night, sir, and here’s mine.” With that we walked side by side to his box, entered it, closed the door, and sat down by the fire.

“I have made up my mind, sir,” he began, bending forward as soon as we were seated, and speaking in a tone but a little above a whisper, “that you shall not have to ask me twice what troubles me. I took you for some one else yesterday evening. That troubles me.”

“That mistake?”

“No. That some one else.”

“Who is it?”

“I don’t know.”

“Like me?”

“I don’t know. I never saw the face. The left arm is across the face, and the right arm is waved,—violently waved. This way.”

I followed his action with my eyes, and it was the action of an arm gesticulating, with the utmost passion and vehemence, “For God’s sake, clear the way!”

“One moonlight night,” said the man, “I was sitting here, when I heard a voice cry, ‘Halloa! Below there!’ I started up, looked from that door, and saw this Some one else standing by the red light near the tunnel, waving as I just now showed you. The voice seemed hoarse with shouting, and it cried, ‘Look out! Look out!’ And then again, ‘Halloa! Below there! Look out!’ I caught up my lamp, turned it on red, and ran towards the figure, calling, ‘What’s wrong? What has happened? Where?’ It stood just outside the blackness of the tunnel. I advanced so close upon it that I wondered at its keeping the sleeve across its eyes. I ran right up at it, and had my hand stretched out to pull the sleeve away, when it was gone.”

“Into the tunnel?” said I.

“No. I ran on into the tunnel, five hundred yards. I stopped, and held my lamp above my head, and saw the figures of the measured distance, and saw the wet stains stealing down the walls and trickling p. 317through the arch. I ran out again faster than I had run in (for I had a mortal abhorrence of the place upon me), and I looked all round the red light with my own red light, and I went up the iron ladder to the gallery atop of it, and I came down again, and ran back here. I telegraphed both ways, ‘An alarm has been given. Is anything wrong?’ The answer came back, both ways, ‘All well.’”

Resisting the slow touch of a frozen finger tracing out my spine, I showed him how that this figure must be a deception of his sense of sight; and how that figures, originating in disease of the delicate nerves that minister to the functions of the eye, were known to have often troubled patients, some of whom had become conscious of the nature of their affliction, and had even proved it by experiments upon themselves. “As to an imaginary cry,” said I, “do but listen for a moment to the wind in this unnatural valley while we speak so low, and to the wild harp it makes of the telegraph wires.”

That was all very well, he returned, after we had sat listening for a while, and he ought to know something of the wind and the wires,—he who so often passed long winter nights there, alone and watching. But he would beg to remark that he had not finished.

I asked his pardon, and he slowly added these words, touching my arm,—

“Within six hours after the Appearance, the memorable accident on this Line happened, and within ten hours the dead and wounded were brought along through the tunnel over the spot where the figure had stood.”

A disagreeable shudder crept over me, but I did my best against it. It was not to be denied, I rejoined, that this was a remarkable coincidence, calculated deeply to impress his mind. But it was unquestionable that remarkable coincidences did continually occur, and they must be taken into account in dealing with such a subject. Though to be sure I must admit, I added (for I thought I saw that he was going to bring the objection to bear upon me), men of common sense did not allow much for coincidences in making the ordinary calculations of life.

He again begged to remark that he had not finished.

I again begged his pardon for being betrayed into interruptions.

“This,” he said, again laying his hand upon my arm, and glancing over his shoulder with hollow eyes, “was just a year ago. Six or seven months passed, and I had recovered from the surprise and shock, when one morning, as the day was breaking, I, standing at the door, looked towards the red light, and saw the spectre again.” He stopped, with a fixed look at me.

“Did it cry out?”

“No. It was silent.”

“Did it wave its arm?”

“No. It leaned against the shaft of the light, with both hands before the face. Like this.”

p. 318Once more I followed his action with my eyes. It was an action of mourning. I have seen such an attitude in stone figures on tombs.

“Did you go up to it?”

“I came in and sat down, partly to collect my thoughts, partly because it had turned me faint. When I went to the door again, daylight was above me, and the ghost was gone.”

“But nothing followed? Nothing came of this?”

He touched me on the arm with his forefinger twice or thrice giving a ghastly nod each time:—

“That very day, as a train came out of the tunnel, I noticed, at a carriage window on my side, what looked like a confusion of hands and heads, and something waved. I saw it just in time to signal the driver, Stop! He shut off, and put his brake on, but the train drifted past here a hundred and fifty yards or more. I ran after it, and, as I went along, heard terrible screams and cries. A beautiful young lady had died instantaneously in one of the compartments, and was brought in here, and laid down on this floor between us.”

Involuntarily I pushed my chair back, as I looked from the boards at which he pointed to himself.

“True, sir. True. Precisely as it happened, so I tell it you.”

I could think of nothing to say, to any purpose, and my mouth was very dry. The wind and the wires took up the story with a long lamenting wail.

He resumed. “Now, sir, mark this, and judge how my mind is troubled. The spectre came back a week ago. Ever since, it has been there, now and again, by fits and starts.”

“At the light?”

“At the Danger-light.”

“What does it seem to do?”

He repeated, if possible with increased passion and vehemence, that former gesticulation of, “For God’s sake, clear the way!”

Then he went on. “I have no peace or rest for it. It calls to me, for many minutes together, in an agonised manner, ‘Below there! Look out! Look out!’ It stands waving to me. It rings my little bell—”

I caught at that. “Did it ring your bell yesterday evening when I was here, and you went to the door?”

“Twice.”

“Why, see,” said I, “how your imagination misleads you. My eyes were on the bell, and my ears were open to the bell, and if I am a living man, it did NOT ring at those times. No, nor at any other time, except when it was rung in the natural course of physical things by the station communicating with you.”

He shook his head. “I have never made a mistake as to that yet, sir. I have never confused the spectre’s ring with the man’s. The ghost’s ring is a strange vibration in the bell that it derives from p. 319nothing else, and I have not asserted that the bell stirs to the eye. I don’t wonder that you failed to hear it. But Iheard it.”

“And did the spectre seem to be there, when you looked out?”

“It WAS there.”

“Both times?”

He repeated firmly: “Both times.”

“Will you come to the door with me, and look for it now?”

He bit his under lip as though he were somewhat unwilling, but arose. I opened the door, and stood on the step, while he stood in the doorway. There was the Danger-light. There was the dismal mouth of the tunnel. There were the high, wet stone walls of the cutting. There were the stars above them.

“Do you see it?” I asked him, taking particular note of his face. His eyes were prominent and strained, but not very much more so, perhaps, than my own had been when I had directed them earnestly towards the same spot.

“No,” he answered. “It is not there.”

“Agreed,” said I.

We went in again, shut the door, and resumed our seats. I was thinking how best to improve this advantage, if it might be called one, when he took up the conversation in such a matter-of-course way, so assuming that there could be no serious question of fact between us, that I felt myself placed in the weakest of positions.

“By this time you will fully understand, sir,” he said, “that what troubles me so dreadfully is the question, What does the spectre mean?”

I was not sure, I told him, that I did fully understand.

“What is its warning against?” he said, ruminating, with his eyes on the fire, and only by times turning them on me. “What is the danger? Where is the danger? There is danger overhanging somewhere on the Line. Some dreadful calamity will happen. It is not to be doubted this third time, after what has gone before. But surely this is a cruel haunting of me. What can I do?”

He pulled out his handkerchief, and wiped the drops from his heated forehead.

“If I telegraph Danger, on either side of me, or on both, I can give no reason for it,” he went on, wiping the palms of his hands. “I should get into trouble, and do no good. They would think I was mad. This is the way it would work,—Message: ‘Danger! Take care!’ Answer: ‘What Danger? Where?’ Message: ‘Don’t know. But, for God’s sake, take care!’ They would displace me. What else could they do?”

His pain of mind was most pitiable to see. It was the mental torture of a conscientious man, oppressed beyond endurance by an unintelligible responsibility involving life.

“When it first stood under the Danger-light,” he went on, putting his dark hair back from his head, and drawing his hands outward p. 320across and across his temples in an extremity of feverish distress, “why not tell me where that accident was to happen,—if it must happen? Why not tell me how it could be averted,—if it could have been averted? When on its second coming it hid its face, why not tell me, instead, ‘She is going to die. Let them keep her at home’? If it came, on those two occasions, only to show me that its warnings were true, and so to prepare me for the third, why not warn me plainly now? And I, Lord help me! A mere poor signal-man on this solitary station! Why not go to somebody with credit to be believed, and power to act?”

When I saw him in this state, I saw that for the poor man’s sake, as well as for the public safety, what I had to do for the time was to compose his mind. Therefore, setting aside all question of reality or unreality between us, I represented to him that whoever thoroughly discharged his duty must do well, and that at least it was his comfort that he understood his duty, though he did not understand these confounding Appearances. In this effort I succeeded far better than in the attempt to reason him out of his conviction. He became calm; the occupations incidental to his post as the night advanced began to make larger demands on his attention: and I left him at two in the morning. I had offered to stay through the night, but he would not hear of it.

That I more than once looked back at the red light as I ascended the pathway, that I did not like the red light, and that I should have slept but poorly if my bed had been under it, I see no reason to conceal. Nor did I like the two sequences of the accident and the dead girl. I see no reason to conceal that either.

But what ran most in my thoughts was the consideration how ought I to act, having become the recipient of this disclosure? I had proved the man to be intelligent, vigilant, painstaking, and exact; but how long might he remain so, in his state of mind? Though in a subordinate position, still he held a most important trust, and would I (for instance) like to stake my own life on the chances of his continuing to execute it with precision?

Unable to overcome a feeling that there would be something treacherous in my communicating what he had told me to his superiors in the Company, without first being plain with himself and proposing a middle course to him, I ultimately resolved to offer to accompany him (otherwise keeping his secret for the present) to the wisest medical practitioner we could hear of in those parts, and to take his opinion. A change in his time of duty would come round next night, he had apprised me, and he would be off an hour or two after sunrise, and on again soon after sunset. I had appointed to return accordingly.

Next evening was a lovely evening, and I walked out early to enjoy it. The sun was not yet quite down when I traversed the field-path near the top of the deep cutting. I would extend my walk for an p. 321hour, I said to myself, half an hour on and half an hour back, and it would then be time to go to my signal-man’s box.

Before pursuing my stroll, I stepped to the brink, and mechanically looked down, from the point from which I had first seen him. I cannot describe the thrill that seized upon me, when, close at the mouth of the tunnel, I saw the appearance of a man, with his left sleeve across his eyes, passionately waving his right arm.

The nameless horror that oppressed me passed in a moment, for in a moment I saw that this appearance of a man was a man indeed, and that there was a little group of other men, standing at a short distance, to whom he seemed to be rehearsing the gesture he made. The Danger-light was not yet lighted. Against its shaft, a little low hut, entirely new to me, had been made of some wooden supports and tarpaulin. It looked no bigger than a bed.

With an irresistible sense that something was wrong,—with a flashing self-reproachful fear that fatal mischief had come of my leaving the man there, and causing no one to be sent to overlook or correct what he did,—I descended the notched path with all the speed I could make.

“What is the matter?” I asked the men.

“Signal-man killed this morning, sir.”

“Not the man belonging to that box?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Not the man I know?”

“You will recognise him, sir, if you knew him,” said the man who spoke for the others, solemnly uncovering his own head, and raising an end of the tarpaulin, “for his face is quite composed.”

“O, how did this happen, how did this happen?” I asked, turning from one to another as the hut closed in again.

“He was cut down by an engine, sir. No man in England knew his work better. But somehow he was not clear of the outer rail. It was just at broad day. He had struck the light, and had the lamp in his hand. As the engine came out of the tunnel, his back was towards her, and she cut him down. That man drove her, and was showing how it happened. Show the gentleman, Tom.”

The man, who wore a rough dark dress, stepped back to his former place at the mouth of the tunnel.

“Coming round the curve in the tunnel, sir,” he said, “I saw him at the end, like as if I saw him down a perspective-glass. There was no time to check speed, and I knew him to be very careful. As he didn’t seem to take heed of the whistle, I shut it off when we were running down upon him, and called to him as loud as I could call.”

“What did you say?”

“I said, ‘Below there! Look out! Look out! For God’s sake, clear the way!’”

I started.

“Ah! it was a dreadful time, sir. I never left off calling to him. p. 322I put this arm before my eyes not to see, and I waved this arm to the last; but it was no use.”

Without prolonging the narrative to dwell on any one of its curious circumstances more than on any other, I may, in closing it, point out the coincidence that the warning of the Engine-Driver included, not only the words which the unfortunate Signal-man had repeated to me as haunting him, but also the words which I myself—not he—had attached, and that only in my own mind, to the gesticulation he had imitated.

FOOTNOTES.

[121] The original has eight chapters, which will be found in All the Year Round, vol. ii., old series; but those not printed here, excepting a page at the close, were not written by Mr. Dickens.

[303] This paper appeared as a chapter “To be taken with a Grain of Salt,” in Doctor Marigold’s Prescriptions.

[312] This story appeared as a portion of the Christmas number for 1866, “Mugby Junction,” of which other portions follow in “Barbox Brothers” and “The Boy at Mugby.”