The Enemy of the World

Donald Trump John Miller Audio TAPE FULL Trump Pretending with Wall Street Journal Reporter

" In her discussion of the impostor, Phyllis Greenacre also cites the case of Titus Oates (1649-1705), who was the great protagonist of the fictitious “Popish Plot” during the reign of Charles II Stuart of England. This plot was supposedly aiming at a Catholic takeover of England with the help of the Stuarts. Fictitious though this report turned out to be, its political effects were most welcome to the pro-Venetian Whig party of the English aristocracy.

Without intelligence networks interested in promoting Titus Oates’ story, he might have been relegated to total obscurity. Oates was a mythomaniac, recounting wild inventions he knew his listeners wanted to hear, all in a desperate bid to attract attention. But there were powerful political forces who found his hallucinations advantageous.

This reminds us once again, as in the case of Joseph Smith, to always look for the interaction between the individual impostor and the organized networks which constitute and assemble the audience which the impostor so urgently desires. Some key excerpts from Greenacre:

“An impostor is not only a liar, but a very special type of liar who imposes on others fabrications of his attainments, position, or worldly possessions. This he may do through misrepresentations of his official (statistical) identity, by presenting himself with a fictitious name, history, and other items of personal identity, either borrowed from some other actual person or fabricated according to some imaginative conception of himself.

There are similar falsifications on that part of his identity belonging to his accomplishments, a plagiarizing on a grand scale, or making claims which are grossly implausible. Imposture appears to contain the hope of getting something material, or some other worldly advantage. While the reverse certainly exists among the distinguished, wealthy, and competent persons who lose themselves in cloaks of obscurity and assumed mediocrity, these come less frequently into sharp focus in the public eye. One suspects, however, that some “hysterical” amnesia is, and dual or multiple personalities are conditions related to imposturous characters. The contrast between the original and the assumed identities may sometimes be not so great in the matter of worldly position, and consequently does not lend itself so readily to the superficial explanation that it has been achieved for direct and material gain. The investigation of even a few instances of imposture – if one has not become emotionally involved in the deception – is sufficient to show how crude though clever many impostors are, how very faulty any scheming is, and how often, in fact, the element of shrewdness is lacking. Rather a quality of showmanship is involved, with its reliance all on the response of an audience to illusions.

“In some of the most celebrated instances of imposture, it indeed appears that the fraud was successful only because many others as well as the perpetrator had a hunger to believe in the fraud, and that any success of such fraudulence depended in fact on strong social as well as individual factors and especial receptivity to the trickery. To this extent those on whom the fraudulence is imposed are not only victims but unconscious conspirators. Its success too is partly a matter of timing. Such combinations of imposturous talent and a peculiar susceptibility of the times to believe in the swindler, who presents the deceptive means of salvation, may account for the great impostures of history. There are, however, instances of the repeated perpetration of frauds under circumstances which give evidence of aprecise content that may seem independent of social factors….

“It is the extraordinary and continued pressure in the impostor to live out his fantasy that demands explanation, a living out which has the force of a delusion, (and in the psychotic may actually appear in that form), but it is ordinarily associated with the ‘formal’ awareness that the claims are false. The sense of reality is characterized by a peculiarly sharp, quick perceptiveness, extraordinarily immediate keenness and responsiveness, especially in the area of the imposture. The over-all utility of the sense of reality is, however, impaired. What is striking in many impostors is that, although they are quick to pick up details and nuances in the lives and activities of those whom they simulate and can sometimes utilize these with great adroitness, they are frequently so utterly obtuse to many ordinary considerations of fact that they give the impression of mere brazenness or stupidity in many aspects of their life peripheral to their impostures….

“The impostor has, then, a specially sharpened sensitivity within the area of his fraud, and identity toward the assumption of which he has a powerful unconscious pressure, beside which his conscious wish, although recognizable, is relatively slight. The unconscious drive heightens his perceptions in a focused area and permits him to ignore or deny other elements of reality which would ordinarily be considered matters of common sense. It is this discrepancy in abilities which makes some impostors such puzzling individuals. Skill and persuasiveness are combined with utter foolishness and stupidity.

“In well-structured impostures this may be described as a struggle between two dominant identities in the individual: the temporarily focused and strongly assertive imposturous one, and the frequently amazingly crude and poorly knit one from which the impostor has emerged. In some instances, however, it is also probable that the imposture cannot be sustained unless there is emotional support from someone who especially believes in and nourishes it. The need for self-betrayal may then he one part of the tendency to revert to a less demanding, more easily sustainable personality, particularly if support is withdrawn.

“The impostor seems to flourish on the success of his exhibitionism. Enjoyment of the limelight and inner triumph of ‘putting something over’ seems inherent, and bespeak the closeness of imposture to voyeurism. Both aspects are represented: pleasure in watching while the voyeur himself is invisible; exultation in being admired and observed as a spectacle. It seems as if the impostor becomes temporarily convinced of the rightness of his assumed character in proportion to the amount of attention he is able to gain from it.

“In the lives of impostors there are circumscribed areas of reaction which approach the delusional. These are clung to when the other elements of the imposture have been relinquished….

“Once an imposturous goal has been glimpsed, the individual seems to behave without need for consistency, but to strive rather for the supremacy of the gains from what can be acted out with sufficient immediate gratification to convince others. For the typical impostor, an audience is absolutely essential. It is from the confirming reaction of his audience that the impostor gets a ‘realistic’ sense of self, a value greater than anything he can otherwise achieve. It is the demand for an audience in which the (false) self is reflected that causes impostures often to become of social significance. Both reality and identity seem to the impostor to be strengthened rather than diminished by the success of the fraudulence of his claims….

“The impostor seems to be repeatedly seeking confirmation of his assumed identity to overcome his sense of helplessness or incompleteness. It is my impression that this is the secret of his appeal to others, and that often especially conscientious people are ‘taken in’ and other impostors as well attracted because of the longing to return to that happy state of omnipotence which adults have had to relinquish….

Just Too WEIRD: Bishop Romney's Mormon Takeover of America:: Polygamy, Theocracy, Subversion

Tarpley Ph D, Webster Griffin

Sounding more like the potentate of some palm-dotted tropical island than a presidential candidate, Donald Trump twice declined to say during the final televised debate whether he would accept the results of the 2016 election.

The billionaire who has cast himself as the law and order candidate seemed ready to commit the democratic felony of refusing to accept defeat at the polls.

The property tycoon, who has regularly used legal action, and the threat of it, to build his business empire, appeared to cling to the hope that he could litigate his way to the White House - if, as seems increasingly likely, voters hand the keys to Hillary Clinton.

In a stab at damage limitation, he has since modified his position. Trump now says he will accept a "clear result," but reserves the right to mount a legal challenge in the event of a "questionable result".

But his original remarks, watched by millions of shell-shocked voters, are hard to walk back. He cannot evoke that old locker room maxim - what happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas.

Unsubstantiated claims that this election is rigged has now become the core message of his stump speech, and it seems targeted at 9 November rather than 8 November - a pre-emptive attempt to rationalise defeat the morning after rather than to mobilise supporters on polling day.

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump (L) speaks as Democratic presidential nominee former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton looks on during the third U.S. presidential debate at the Thomas Mack Center on October 19, 2016 in Las Vegas, Nevada

Not only does this approach seem irresponsible but also counter-productive, for it runs the risk of depressing Republican turnout. Why vote, his more conspiratorial-minded supporters might think, if the fix is already in?

Threats of legal challenges may well be Trumpian bluster. His promise to sue the New York Times for publishing accusations from women that he allegedly molested them have so far come to nought.

As for saying during the debate he would hold the electorate in "suspense", it sounded like a fading reality TV star clamorous for viewers, fearful his show was about to be cancelled because of sliding ratings.

Grace in defeat is not just a feature of the American system, but one of its more elegant pillars.

John McCain's concession speech in 2008 is widely regarded as the noblest of his career. John Kerry accepted the outcome in 2004, despite claims of voter irregularities in the decisive battleground state of Ohio.

In 1960, when only 113,000 votes out of the 68 million cast separated the candidates, Richard Nixon conceded, even though he would have been forgiven for mounting a more forceful legal challenge, given the allegations of voter fraud in Texas and Illinois.

Trump says will accept result 'if I win'

There, Chicago's mayor Richard Daley was alleged to have conjured up enough phantom votes to make sure Illinois remained in John F Kennedy's column.

GOP officials carried out investigations and mounted legal challenges in a number of battleground states, but Nixon was publicly acquiescent. The then vice-president told friends he did not want to come across as a sore loser, nor spark a constitutional crisis.

In the aftermath of the Las Vegas debate, Trump surrogates cited the more recent example of the contested 2000 election, when Al Gore dramatically withdrew his concession on election night while in his limousine on the way to deliver a speech accepting defeat.

But Gore wasn't challenging the results of the election. Rather, he was calling for a recount of the votes in Florida.

At the end of the interminable legal battle that followed, when five of the nine Supreme Court justices ruled in favour of George W Bush, Al Gore accepted the outcome, even though some aides wanted him to fight on.

"Tonight, for the sake of our unity as a people and the strength of our democracy, I offer my concession," Gore told the nation.

People in Times Square watch Vice President Al Gore concede the race for president to George W. Bush December 13, 2000

Al Gore concedes on December 13, 2000

Though clearly crest-fallen, he quoted Senator Stephen Douglas's reaction to his defeat in 1860 to Abraham Lincoln: "Partisan feeling must yield to patriotism." Trump may be temperamentally incapable of displaying that kind of magnanimity.

The billionaire's campaign staff is clearly worried that Trump has ruined any remaining chance he had of winning. Senior GOP figures, like John McCain, are enraged at the damage he has done to the Republican Party.

But the broader problem is that he has brought American democracy into disrepute by showing such contempt for its most basic tenet, that the will of the people should be respected and adhered to.

Those who still have faith in the US political system - a dwindling number judging by the historically high disapproval ratings for both candidates and Congress - might try to write off Donald Trump as an aberration.

The truth is, however, that his debate comments, which will echo down the years, mark the culmination of a trend in US politics decades in the making.

Politicians from both parties have sought to delegitimise the victories of their opponents, and to deny the incoming president a mandate.

Though individual candidates, like John McCain and John Kerry, have displayed high-mindedness in defeat, their respective parties have not been anywhere near as yielding. The opposite is true.

In modern times, this can be traced back to the 1992 election, when Republicans immediately questioned the legitimacy of Bill Clinton because he won the presidency with such a small share of the popular vote - just 43%, the second lowest share of any winning candidate in the 20th Century.

Republicans felt aggrieved that George Herbert Walker Bush had been cheated out of a second term by the third party candidate Ross Perot - although political scientists believe that the Texan billionaire attracted just as many Democratic votes as Republican.

Much of the impetus for the impeachment of President Clinton in 1998, following the Monica Lewinsky scandal, stemmed from the manner of his victory in 1992. Many Republicans, chief among them congressman trying to drive him from office, had never accepted his legitimacy as president.

Impeachment vote in Senate

The Senate votes on Bill Clinton's impeachment

Following the disputed 2000 election, Democrats took the same dim view of George W Bush.

When the senior Democratic congressman Dick Gephardt appeared on NBC's Meet the Press in the aftermath of the Supreme Court ruling, he acknowledged that George W Bush would be the next president of the United States, but pointedly turned down the invitation to describe him as "the legitimate president of the United States".

Other Democrats, condemning a partisan Supreme Court for voting along partisan lines, spoke at the time of an American coup d'etat.

The birther movement, of which Donald Trump became the figurehead, was founded on the false idea that Barack Obama's presidency was illegitimate because he was not born in America.

Republicans on Capitol Hill, who rejected the racism of birtherism, nonetheless showed little or no respect for Obama's mandate, even though he won with more than 50% of the vote both in 2008 and 2012.

Repeatedly, they have used the checks and balances offered by the constitution to thwart and block their nemesis. So much so that gridlock has become the paralysing norm in Washington.

Portrait of the 19th U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes. (1822-1893)

"His Fraudulency" Rutherford B Hayes

Historians of the 19th Century will tell you that the notion of "imposter presidents" is nothing new.

Rutherford B Hayes, the winner of a disputed election in 1876, was known as "His Fraudulency".

Now though we have reached the point where the last three presidents, Clinton, Bush and Obama, have been cast by opponents as imposter presidents.

America's broken politics, even more so than its malfunctioning economy, provided the seedbed for Donald Trump's rise, but in refusing to graciously accept defeat he is threatening to break the system still further.

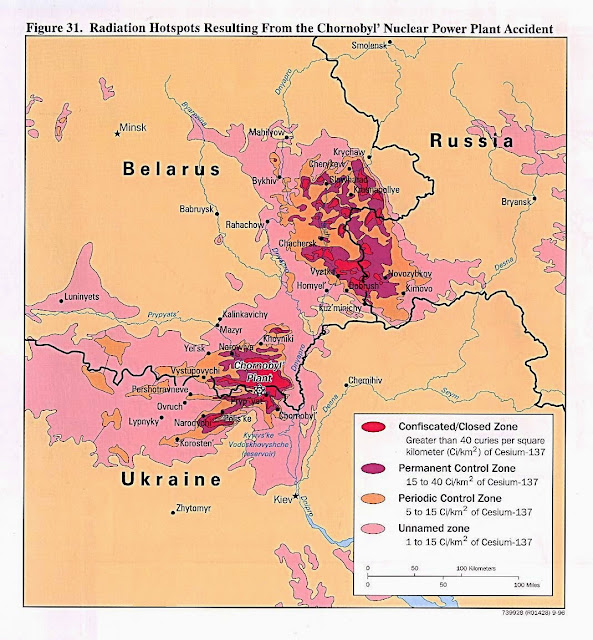

His critics will see this as further proof that his campaign is in meltdown. But the broader fear is of a post-election political Chernobyl that will further contaminate an already poisonous system for decades to come.

“More than a medical scientific problem, AIDS is a sociopolitical IMPOSITION.” "