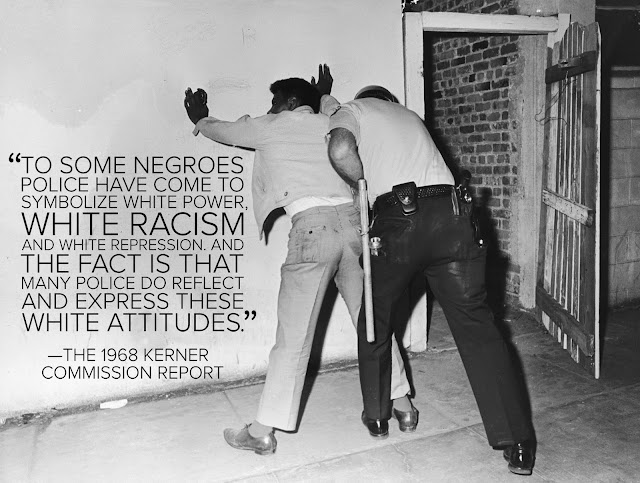

"CIVILIZATION’S GOING TO PIECES,” he remarks. He is in polite company, gathered with friends around a bottle of wine in the late-afternoon sun, chatting and gossiping. “I’ve gotten to be a terrible pessimist about things. Have you read The Rise of the Colored Empires by this man Goddard?” They hadn’t. “Well, it’s a fine book, and everybody ought to read it. The idea is if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged. It’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved.”

Also see:

State of the Union: Race

Hua Hsu and Ta-Nehisi Coates discuss Obama, football, hip-hop, and the elusive notion of a "post-racial" society.

State of the Union: Race

Hua Hsu and Ta-Nehisi Coates discuss Obama, football, hip-hop, and the elusive notion of a "post-racial" society.

He is Tom Buchanan, a character in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, a book that nearly everyone who passes through the American education system is compelled to read at least once. Although Gatsby doesn’t gloss as a book on racial anxiety—it’s too busy exploring a different set of anxieties entirely—Buchanan was hardly alone in feeling besieged. The book by “this man Goddard” had a real-world analogue: Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy, published in 1920, five years before Gatsby. Nine decades later, Stoddard’s polemic remains oddly engrossing. He refers to World War I as the “White Civil War” and laments the “cycle of ruin” that may result if the “white world” continues its infighting. The book features a series of foldout maps depicting the distribution of “color” throughout the world and warns, “Colored migration is a universal peril, menacing every part of the white world.”

As briefs for racial supremacy go, The Rising Tide of Color is eerily serene. Its tone is scholarly and gentlemanly, its hatred rationalized and, in Buchanan’s term, “scientific.” And the book was hardly a fringe phenomenon. It was published by Scribner, also Fitzgerald’s publisher, and Stoddard, who received a doctorate in history from Harvard, was a member of many professional academic associations. It was precisely the kind of book that a 1920s man of Buchanan’s profile—wealthy, Ivy League–educated, at once pretentious and intellectually insecure—might have been expected to bring up in casual conversation.

As white men of comfort and privilege living in an age of limited social mobility, of course, Stoddard and the Buchanans in his audience had nothing literal to fear. Their sense of dread hovered somewhere above the concerns of everyday life. It was linked less to any immediate danger to their class’s political and cultural power than to the perceived fraying of the fixed, monolithic identity of whiteness that sewed together the fortunes of the fair-skinned.

From the hysteria over Eastern European immigration to the vibrant cultural miscegenation of the Harlem Renaissance, it is easy to see how this imagined worldwide white kinship might have seemed imperiled in the 1920s. There’s no better example of the era’s insecurities than the 1923 Supreme Court case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, in which an Indian American veteran of World War I sought to become a naturalized citizen by proving that he was Caucasian. The Court considered new anthropological studies that expanded the definition of the Caucasian race to include Indians, and the justices even agreed that traces of “Aryan blood” coursed through Thind’s body. But these technicalities availed him little. The Court determined that Thind was not white “in accordance with the understanding of the common man” and therefore could be excluded from the “statutory category” of whiteness. Put another way: Thind was white, in that he was Caucasian and even Aryan. But he was notwhite in the way Stoddard or Buchanan were white.

The ’20s debate over the definition of whiteness—a legal category? a commonsense understanding? a worldwide civilization?—took place in a society gripped by an acute sense of racial paranoia, and it is easy to regard these episodes as evidence of how far we have come. But consider that these anxieties surfaced when whiteness was synonymous with the American mainstream, when threats to its status were largely imaginary. What happens once this is no longer the case—when the fears of Lothrop Stoddard and Tom Buchanan are realized, and white people actually become an American minority?

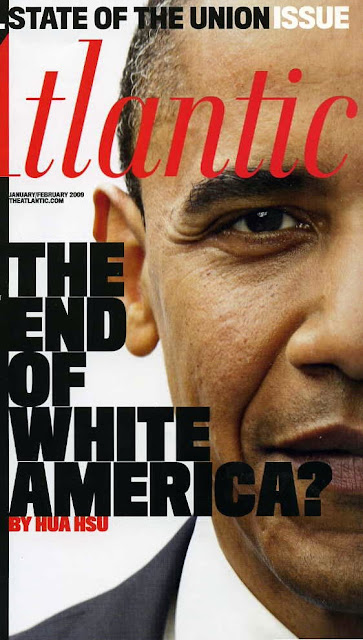

Whether you describe it as the dawning of a post-racial age or just the end of white America, we’re approaching a profound demographic tipping point. According to an August 2008 report by the U.S. Census Bureau, those groups currently categorized as racial minorities—blacks and Hispanics, East Asians and South Asians—will account for a majority of the U.S. population by the year 2042. Among Americans under the age of 18, this shift is projected to take place in 2023, which means that every child born in the United States from here on out will belong to the first post-white generation.

Obviously, steadily ascending rates of interracial marriage complicate this picture, pointing toward what Michael Lind has described as the “beiging” of America. And it’s possible that “beige Americans” will self-identify as “white” in sufficient numbers to push the tipping point further into the future than the Census Bureau projects. But even if they do, whiteness will be a label adopted out of convenience and even indifference, rather than aspiration and necessity. For an earlier generation of minorities and immigrants, to be recognized as a “white American,” whether you were an Italian or a Pole or a Hungarian, was to enter the mainstream of American life; to be recognized as something else, as theThind case suggests, was to be permanently excluded. As Bill Imada, head of the IW Group, a prominent Asian American communications and marketing company, puts it: “I think in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, [for] anyone who immigrated, the aspiration was to blend in and be as American as possible so that white America wouldn’t be intimidated by them. They wanted to imitate white America as much as possible: learn English, go to church, go to the same schools.”

Today, the picture is far more complex. To take the most obvious example, whiteness is no longer a precondition for entry into the highest levels of public office. The son of Indian immigrants doesn’t have to become “white” in order to be elected governor of Louisiana. A half-Kenyan, half-Kansan politician can self-identify as black and be elected president of the United States.

As a purely demographic matter, then, the “white America” that Lothrop Stoddard believed in so fervently may cease to exist in 2040, 2050, or 2060, or later still. But where the culture is concerned, it’s already all but finished. Instead of the long-standing model of assimilation toward a common center, the culture is being remade in the image of white America’s multiethnic, multicolored heirs.

For some, the disappearance of this centrifugal core heralds a future rich with promise. In 1998, President Bill Clinton, in a now-famous address to students at Portland State University, remarked:

Today, largely because of immigration, there is no majority race in Hawaii or Houston or New York City. Within five years, there will be no majority race in our largest state, California. In a little more than 50 years, there will be no majority race in the United States. No other nation in history has gone through demographic change of this magnitude in so short a time ... [These immigrants] are energizing our culture and broadening our vision of the world. They are renewing our most basic values and reminding us all of what it truly means to be American.

Not everyone was so enthused. Clinton’s remarks caught the attention of another anxious Buchanan—Pat Buchanan, the conservative thinker. Revisiting the president’s speech in his 2001 book, The Death of the West, Buchanan wrote: “Mr. Clinton assured us that it will be a better America when we are all minorities and realize true ‘diversity.’ Well, those students [at Portland State] are going to find out, for they will spend their golden years in a Third World America.”

Today, the arrival of what Buchanan derided as “Third World America” is all but inevitable. What will the new mainstream of America look like, and what ideas or values might it rally around? What will it mean to be white after “whiteness” no longer defines the mainstream? Will anyone mourn the end of white America? Will anyone try to preserve it?

|

ANOTHER MOMENT FROM The Great Gatsby: as Fitzgerald’s narrator and Gatsby drive across the Queensboro Bridge into Manhattan, a car passes them, and Nick Carraway notices that it is a limousine “driven by a white chauffeur, in which sat three modish negroes, two bucks and a girl.” The novelty of this topsy-turvy arrangement inspires Carraway to laugh aloud and think to himself, “Anything can happen now that we’ve slid over this bridge, anything at all …”

For a contemporary embodiment of the upheaval that this scene portended, consider Sean Combs, a hip-hop mogul and one of the most famous African Americans on the planet. Combs grew up during hip-hop’s late-1970s rise, and he belongs to the first generation that could safely make a living working in the industry—as a plucky young promoter and record-label intern in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and as a fashion designer, artist, and music executive worth hundreds of millions of dollars a brief decade later.

In the late 1990s, Combs made a fascinating gesture toward New York’s high society. He announced his arrival into the circles of the rich and powerful not by crashing their parties, but by inviting them into his own spectacularly over-the-top world. Combs began to stage elaborate annual parties in the Hamptons, not far from where Fitzgerald’s novel takes place. These “white parties”—attendees are required to wear white—quickly became legendary for their opulence (in 2004, Combs showcased a 1776 copy of the Declaration of Independence) as well as for the cultures-colliding quality of Hamptons elites paying their respects to someone so comfortably nouveau riche. Prospective business partners angled to get close to him and praised him as a guru of the lucrative “urban” market, while grateful partygoers hailed him as a modern-day Gatsby.

“Have I read The Great Gatsby?” Combs said to a London newspaper in 2001. “I am the Great Gatsby.”

Yet whereas Gatsby felt pressure to hide his status as an arriviste, Combs celebrated his position as an outsider-insider—someone who appropriates elements of the culture he seeks to join without attempting to assimilate outright. In a sense, Combs was imitating the old WASP establishment; in another sense, he was subtly provoking it, by over-enunciating its formality and never letting his guests forget that there was something slightly off about his presence. There’s a silent power to throwing parties where the best-dressed man in the room is also the one whose public profile once consisted primarily of dancing in the background of Biggie Smalls videos. (“No one would ever expect a young black man to be coming to a party with the Declaration of Independence, but I got it, and it’s coming with me,” Combs joked at his 2004 party, as he made the rounds with the document, promising not to spill champagne on it.)

In this regard, Combs is both a product and a hero of the new cultural mainstream, which prizes diversity above all else, and whose ultimate goal is some vague notion of racial transcendence, rather than subversion or assimilation. Although Combs’s vision is far from representative—not many hip-hop stars vacation in St. Tropez with a parasol-toting manservant shading their every step—his industry lies at the heart of this new mainstream. Over the past 30 years, few changes in American culture have been as significant as the rise of hip-hop. The genre has radically reshaped the way we listen to and consume music, first by opposing the pop mainstream and then by becoming it. From its constant sampling of past styles and eras—old records, fashions, slang, anything—to its mythologization of the self-made black antihero, hip-hop is more than a musical genre: it’s a philosophy, a political statement, a way of approaching and remaking culture. It’s a lingua franca not just among kids in America, but also among young people worldwide. And its economic impact extends beyond the music industry, to fashion, advertising, and film. (Consider the producer Russell Simmons—the ur-Combs and a music, fashion, and television mogul—or the rapper 50 Cent, who has parlayed his rags-to-riches story line into extracurricular successes that include a clothing line; book, video-game, and film deals; and a startlingly lucrative partnership with the makers of Vitamin Water.)

But hip-hop’s deepest impact is symbolic. During popular music’s rise in the 20th century, white artists and producers consistently “mainstreamed” African American innovations. Hip-hop’s ascension has been different. Eminem notwithstanding, hip-hop never suffered through anything like an Elvis Presley moment, in which a white artist made a musical form safe for white America. This is no dig at Elvis—the constrictive racial logic of the 1950s demanded the erasure of rock and roll’s black roots, and if it hadn’t been him, it would have been someone else. But hip-hop—the sound of the post- civil-rights, post-soul generation—found a global audience on its own terms.

Today, hip-hop’s colonization of the global imagination, from fashion runways in Europe to dance competitions in Asia, is Disney-esque. This transformation has bred an unprecedented cultural confidence in its black originators. Whiteness is no longer a threat, or an ideal: it’s kitsch to be appropriated, whether with gestures like Combs’s “white parties” or the trickle-down epidemic of collared shirts and cuff links currently afflicting rappers. And an expansive multiculturalism is replacing the us-against-the-world bunker mentality that lent a thrilling edge to hip-hop’s mid-1990s rise.

Peter Rosenberg, a self-proclaimed “nerdy Jewish kid” and radio personality on New York’s Hot 97 FM—and a living example of how hip-hop has created new identities for its listeners that don’t fall neatly along lines of black and white—shares another example: “I interviewed [the St. Louis rapper] Nelly this morning, and he said it’s now very cool and in to have multicultural friends. Like you’re not really considered hip or ‘you’ve made it’ if you’re rolling with all the same people.”

Just as Tiger Woods forever changed the country-club culture of golf, and Will Smith confounded stereotypes about the ideal Hollywood leading man, hip-hop’s rise is helping redefine the American mainstream, which no longer aspires toward a single iconic image of style or class. Successful network-television shows like Lost, Heroes, and Grey’s Anatomy feature wildly diverse casts, and an entire genre of half-hour comedy, from The Colbert Report to The Office, seems dedicated to having fun with the persona of the clueless white male. The youth market is following the same pattern: consider theCheetah Girls, a multicultural, multiplatinum, multiplatform trio of teenyboppers who recently starred in their third movie, or Dora the Explorer, the precocious bilingual 7-year-old Latina adventurer who is arguably the most successful animated character on children’s television today. In a recent address to the Association of Hispanic Advertising Agencies, Brown Johnson, the Nickelodeon executive who has overseen Dora’s rise, explained the importance of creating a character who does not conform to “the white, middle-class mold.” When Johnson pointed out that Dora’s wares were outselling Barbie’s in France, the crowd hooted in delight.

Pop culture today rallies around an ethic of multicultural inclusion that seems to value every identity—except whiteness. “It’s become harder for the blond-haired, blue-eyed commercial actor,” remarks Rochelle Newman-Carrasco, of the Hispanic marketing firm Enlace. “You read casting notices, and they like to cast people with brown hair because they could be Hispanic. The language of casting notices is pretty shocking because it’s so specific: ‘Brown hair, brown eyes, could look Hispanic.’ Or, as one notice put it: ‘Ethnically ambiguous.’”

“I think white people feel like they’re under siege right now—like it’s not okay to be white right now, especially if you’re a white male,” laughs Bill Imada, of the IW Group. Imada and Newman-Carrasco are part of a movement within advertising, marketing, and communications firms to reimagine the profile of the typical American consumer. (Tellingly, every person I spoke with from these industries knew the Census Bureau’s projections by heart.)

“There’s a lot of fear and a lot of resentment,” Newman-Carrasco observes, describing the flak she caught after writing an article for a trade publication on the need for more-diverse hiring practices. “I got a response from a friend—he’s, like, a 60-something white male, and he’s been involved with multicultural recruiting,” she recalls. “And he said, ‘I really feel like the hunted. It’s a hard time to be a white man in America right now, because I feel like I’m being lumped in with all white males in America, and I’ve tried to do stuff, but it’s a tough time.’”

“I always tell the white men in the room, ‘We need you,’” Imada says. “We cannot talk about diversity and inclusion and engagement without you at the table. It’s okay to be white!

“But people are stressed out about it. ‘We used to be in control! We’re losing control!’”

IF THEY’RE RIGHT—if white America is indeed “losing control,” and if the future will belong to people who can successfully navigate a post-racial, multicultural landscape—then it’s no surprise that many white Americans are eager to divest themselves of their whiteness entirely.

For some, this renunciation can take a radical form. In 1994, a young graffiti artist and activist named William “Upski” Wimsatt, the son of a university professor, published Bomb the Suburbs, the spiritual heir to Norman Mailer’s celebratory 1957 essay, “The White Negro.” Wimsatt was deeply committed to hip-hop’s transformative powers, going so far as to embrace the status of the lowly “wigger,” a pejorative term popularized in the early 1990s to describe white kids who steep themselves in black culture. Wimsatt viewed the wigger’s immersion in two cultures as an engine for change. “If channeled in the right way,” he wrote, “the wigger can go a long way toward repairing the sickness of race in America.”

Wimsatt’s painfully earnest attempts to put his own relationship with whiteness under the microscope coincided with the emergence of an academic discipline known as “whiteness studies.” In colleges and universities across the country, scholars began examining the history of “whiteness” and unpacking its contradictions. Why, for example, had the Irish and the Italians fallen beyond the pale at different moments in our history? Were Jewish Americans white? And, as the historian Matthew Frye Jacobson asked, “Why is it that in the United States, a white woman can have black children but a black woman cannot have white children?”

Much like Wimsatt, the whiteness-studies academics—figures such as Jacobson, David Roediger, Eric Lott, and Noel Ignatiev—were attempting to come to terms with their own relationships with whiteness, in its past and present forms. In the early 1990s, Ignatiev, a former labor activist and the author of How the Irish Became White, set out to “abolish” the idea of the white race by starting the New Abolitionist Movement and founding a journal titled Race Traitor. “There is nothing positive about white identity,” he wrote in 1998. “As James Baldwin said, ‘As long as you think you’re white, there’s no hope for you.’”

Although most white Americans haven’t read Bomb the Suburbs or Race Traitor, this view of whiteness as something to be interrogated, if not shrugged off completely, has migrated to less academic spheres. The perspective of the whiteness-studies academics is commonplace now, even if the language used to express it is different.

“I get it: as a straight white male, I’m the worst thing on Earth,” Christian Lander says. Lander is a Canadian-born, Los Angeles–based satirist who in January 2008 started a blog called Stuff White People Like (stuffwhitepeoplelike.com), which pokes fun at the manners and mores of a specific species of young, hip, upwardly mobile whites. (He has written more than 100 entries about whites’ passion for things like bottled water, “the idea of soccer,” and “being the only white person around.”) At its best, Lander’s site—which formed the basis for a recently published book of the same name (reviewed in the October 2008 Atlantic)—is a cunningly precise distillation of the identity crisis plaguing well-meaning, well-off white kids in a post-white world.

“Like, I’m aware of all the horrible crimes that my demographic has done in the world,” Lander says. “And there’s a bunch of white people who are desperate—desperate—to say, ‘You know what? My skin’s white, but I’m not one of the white people who’s destroying the world.’”

For Lander, whiteness has become a vacuum. The “white identity” he limns on his blog is predicated on the quest for authenticity—usually other people’s authenticity. “As a white person, you’re just desperate to find something else to grab onto. You’re jealous! Pretty much every white person I grew up with wished they’d grown up in, you know, an ethnic home that gave them a second language. White culture is Family Ties and Led Zeppelin and Guns N’ Roses—like, this is white culture. This is all we have.”

Lander’s “white people” are products of a very specific historical moment, raised by well-meaning Baby Boomers to reject the old ideal of white American gentility and to embrace diversity and fluidity instead. (“It’s strange that we are the kids of Baby Boomers, right? How the hell do you rebel against that? Like, your parents will march against the World Trade Organization next to you. They’ll have bigger white dreadlocks than you. What do you do?”) But his lighthearted anthropology suggests that the multicultural harmony they were raised to worship has bred a kind of self-denial.

Matt Wray, a sociologist at Temple University who is a fan of Lander’s humor, has observed that many of his white students are plagued by a racial-identity crisis: “They don’t care about socioeconomics; they care about culture. And to be white is to be culturally broke. The classic thing white students say when you ask them to talk about who they are is, ‘I don’t have a culture.’ They might be privileged, they might be loaded socioeconomically, but they feel bankrupt when it comes to culture … They feel disadvantaged, and they feel marginalized. They don’t have a culture that’s cool or oppositional.” Wray says that this feeling of being culturally bereft often prevents students from recognizing what it means to be a child of privilege—a strange irony that the first wave of whiteness-studies scholars, in the 1990s, failed to anticipate.

Of course, the obvious material advantages that come with being born white—lower infant-mortality rates and easier-to-acquire bank loans, for example—tend to undercut any sympathy that this sense of marginalization might generate. And in the right context, cultural-identity crises can turn well-meaning whites into instant punch lines. Consider ego trip’s The (White) Rapper Show, a brilliant and critically acclaimed reality show that VH1 debuted in 2007. It depicted 10 (mostly hapless) white rappers living together in a dilapidated house—dubbed “Tha White House”—in the South Bronx. Despite the contestants’ best intentions, each one seemed like a profoundly confused caricature, whether it was the solemn graduate student committed to fighting racism or the ghetto-obsessed suburbanite who had, seemingly by accident, named himself after the abolitionist John Brown.

Similarly, Smirnoff struck marketing gold in 2006 with a viral music video titled “Tea Partay,” featuring a trio of strikingly bad, V-neck-sweater-clad white rappers called the Prep Unit. “Haters like to clown our Ivy League educations / But they’re just jealous ’cause our families run the nation,” the trio brayed, as a pair of bottle-blond women in spiffy tennis whites shimmied behind them. There was no nonironic way to enjoy the video; its entire appeal was in its self-aware lampooning of WASPculture: verdant country clubs, “old money,” croquet, popped collars, and the like.

“The best defense is to be constantly pulling the rug out from underneath yourself,” Wray remarks, describing the way self-aware whites contend with their complicated identity. “Beat people to the punch. You’re forced as a white person into a sense of ironic detachment. Irony is what fuels a lot of white subcultures. You also see things like Burning Man, when a lot of white people are going into the desert and trying to invent something that is entirely new and not a form of racial mimicry. That’s its own kind of flight from whiteness. We’re going through a period where whites are really trying to figure out: Who are we?”

THE “FLIGHT FROM WHITENESS” of urban, college-educated, liberal whites isn’t the only attempt to answer this question. You can flee into whiteness as well. This can mean pursuing the authenticity of an imagined past: think of the deliberately white-bread world of Mormon America, where the ’50s never ended, or the anachronistic WASP entitlement flaunted in books like last year’s A Privileged Life: Celebrating WASP Style, a handsome coffee-table book compiled by Susanna Salk, depicting a world of seersucker blazers, whale pants, and deck shoes. (What the book celebrates is the “inability to be outdone,” and the “self-confidence and security that comes with it,” Salk tells me. “That’s why I call it ‘privilege.’ It’s this privilege of time, of heritage, of being in a place longer than anybody else.”) But these enclaves of preserved-in-amber whiteness are likely to be less important to the American future than the construction of whiteness as a somewhat pissed-off minority culture.

This notion of a self-consciously white expression of minority empowerment will be familiar to anyone who has come across the comedian Larry the Cable Guy—he of “Farting Jingle Bells”—or witnessed the transformation of Detroit-born-and-bred Kid Rock from teenage rapper into “American Bad Ass” southern-style rocker. The 1990s may have been a decade when multiculturalism advanced dramatically—when American culture became “colorized,” as the critic Jeff Chang put it—but it was also an era when a very different form of identity politics crystallized. Hip-hop may have provided the decade’s soundtrack, but the highest-selling artist of the ’90s was Garth Brooks. Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods may have been the faces of athletic superstardom, but it was NASCAR that emerged as professional sports’ fastest-growing institution, with ratings second only to the NFL’s.

As with the unexpected success of the apocalyptic Left Behind novels, or the Jeff Foxworthy–organized Blue Collar Comedy Tour, the rise of country music and auto racing took place well off the American elite’s radar screen. (None of Christian Lander’s white people would be caught dead at a NASCARrace.) These phenomena reflected a growing sense of cultural solidarity among lower-middle-class whites—a solidarity defined by a yearning for American “authenticity,” a folksy realness that rejects the global, the urban, and the effete in favor of nostalgia for “the way things used to be.”

Like other forms of identity politics, white solidarity comes complete with its own folk heroes, conspiracy theories (Barack Obama is a secret Muslim! The U.S. is going to merge with Canada and Mexico!), and laundry lists of injustices. The targets and scapegoats vary—from multiculturalism and affirmative action to a loss of moral values, from immigration to an economy that no longer guarantees the American worker a fair chance—and so do the political programs they inspire. (Ross Perot and Pat Buchanan both tapped into this white identity politics in the 1990s; today, its tribunes run the ideological gamut, from Jim Webb to Ron Paul to Mike Huckabee to Sarah Palin.) But the core grievance, in each case, has to do with cultural and socioeconomic dislocation—the sense that the system that used to guarantee the white working class some stability has gone off-kilter.

Wray is one of the founders of what has been called “white-trash studies,” a field conceived as a response to the perceived elite-liberal marginalization of the white working class. He argues that the economic downturn of the 1970s was the precondition for the formation of an “oppositional” and “defiant” white-working-class sensibility—think of the rugged, anti-everything individualism of 1977’sSmokey and the Bandit. But those anxieties took their shape from the aftershocks of the identity-based movements of the 1960s. “I think that the political space that the civil-rights movement opens up in the mid-1950s and ’60s is the transformative thing,” Wray observes. “Following the black-power movement, all of the other minority groups that followed took up various forms of activism, including brown power and yellow power and red power. Of course the problem is, if you try and have a ‘white power’ movement, it doesn’t sound good.”

The result is a racial pride that dares not speak its name, and that defines itself through cultural cues instead—a suspicion of intellectual elites and city dwellers, a preference for folksiness and plainness of speech (whether real or feigned), and the association of a working-class white minority with “the real America.” (In the Scots-Irish belt that runs from Arkansas up through West Virginia, the most common ethnic label offered to census takers is “American.”) Arguably, this white identity politics helped swing the 2000 and 2004 elections, serving as the powerful counterpunch to urban white liberals, and the McCain-Palin campaign relied on it almost to the point of absurdity (as when a McCain surrogate dismissed Northern Virginia as somehow not part of “the real Virginia”) as a bulwark against the threatening multiculturalism of Barack Obama. Their strategy failed, of course, but it’s possible to imagine white identity politics growing more potent and more forthright in its racial identifications in the future, as “the real America” becomes an ever-smaller portion of, well, the real America, and as the soon-to-be white minority’s sense of being besieged and disdained by a multicultural majority grows apace.

This vision of the aggrieved white man lost in a world that no longer values him was given its most vivid expression in the 1993 film Falling Down. Michael Douglas plays Bill Foster, a downsized defense worker with a buzz cut and a pocket protector who rampages through a Los Angeles overrun by greedy Korean shop-owners and Hispanic gangsters, railing against the eclipse of the America he used to know. (The film came out just eight years before California became the nation’s first majority-minority state.) Falling Down ends with a soulful police officer apprehending Foster on the Santa Monica Pier, at which point the middle-class vigilante asks, almost innocently: “I’m the bad guy?”

BUT THIS IS a nightmare vision. Of course most of America’s Bill Fosters aren’t the bad guys—just as civilization is not, in the words of Tom Buchanan, “going to pieces” and America is not, in the phrasing of Pat Buchanan, going “Third World.” The coming white minority does not mean that the racial hierarchy of American culture will suddenly become inverted, as in 1995’s White Man’s Burden, an awful thought experiment of a film, starring John Travolta, that envisions an upside-down world in which whites are subjugated to their high-class black oppressors. There will be dislocations and resentments along the way, but the demographic shifts of the next 40 years are likely to reduce the power of racial hierarchies over everyone’s lives, producing a culture that’s more likely than any before to treat its inhabitants as individuals, rather than members of a caste or identity group.

Consider the world of advertising and marketing, industries that set out to mold our desires at a subconscious level. Advertising strategy once assumed a “general market”—“a code word for ‘white people,’” jokes one ad executive—and smaller, mutually exclusive, satellite “ethnic markets.” In recent years, though, advertisers have begun revising their assumptions and strategies in anticipation of profound demographic shifts. Instead of herding consumers toward a discrete center, the goal today is to create versatile images and campaigns that can be adapted to highly individualized tastes. (Think of the dancing silhouettes in Apple’s iPod campaign, which emphasizes individuality and diversity without privileging—or even representing—any specific group.)

At the moment, we can call this the triumph of multiculturalism, or post-racialism. But just aswhiteness has no inherent meaning—it is a vessel we fill with our hopes and anxieties—these terms may prove equally empty in the long run. Does being post-racial mean that we are past race completely, or merely that race is no longer essential to how we identify ourselves? Karl Carter, of Atlanta’s youth-oriented GTM Inc. (Guerrilla Tactics Media), suggests that marketers and advertisers would be better off focusing on matrices like “lifestyle” or “culture” rather than race or ethnicity. “You’ll have crazy in-depth studies of the white consumer or the Latino consumer,” he complains. “But how do skaters feel? How do hip-hoppers feel?”

The logic of online social networking points in a similar direction. The New York University sociologist Dalton Conley has written of a “network nation,” in which applications like Facebook and MySpace create “crosscutting social groups” and new, flexible identities that only vaguely overlap with racial identities. Perhaps this is where the future of identity after whiteness lies—in a dramatic departure from the racial logic that has defined American culture from the very beginning. What Conley, Carter, and others are describing isn’t merely the displacement of whiteness from our cultural center; they’re describing a social structure that treats race as just one of a seemingly infinite number of possible self-identifications.

From the archives:

The Freedmen's Bureau (March 1901)

"The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line..." By W.E.B. DuBois

The Freedmen's Bureau (March 1901)

"The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line..." By W.E.B. DuBois

The problem of the 20th century, W. E. B. DuBois famously predicted, would be the problem of the color line. Will this continue to be the case in the 21st century, when a black president will govern a country whose social networks increasingly cut across every conceivable line of identification? The ruling of United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind no longer holds weight, but its echoes have been inescapable: we aspire to be post-racial, but we still live within the structures of privilege, injustice, and racial categorization that we inherited from an older order. We can talk about defining ourselves by lifestyle rather than skin color, but our lifestyle choices are still racially coded. We know, more or less, that race is a fiction that often does more harm than good, and yet it is something we cling to without fully understanding why—as a social and legal fact, a vague sense of belonging and place that we make solid through culture and speech.

But maybe this is merely how it used to be—maybe this is already an outdated way of looking at things. “You have a lot of young adults going into a more diverse world,” Carter remarks. For the young Americans born in the 1980s and 1990s, culture is something to be taken apart and remade in their own image. “We came along in a generation that didn’t have to follow that path of race,” he goes on. “We saw something different.” This moment was not the end of white America; it was not the end of anything. It was a bridge, and we crossed it.

This article available online at:

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/01/the-end-of-white-america/307208/