"I have not become the King's First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire. ...

I am proud to be a member of that vast commonwealth and society of nations and communities gathered in and around the ancient British monarchy, without which the good cause might well have perished from the face of the earth.

Here we are, and here we stand, a veritable rock of salvation in this drifting world...."

The Fall of Singapore : The Great Betrayal from Spike EP on Vimeo.

"I regard the attached to be most serious... Here we are, about to be at war with Japan... Here are all these Englishmen - two of whom I know personally - running around, collecting information for the Japanese..."

- Winston Churchill washes his hands

Summer 1941

"Though it's largely forgotten now, Japan had been an ally of Britain throughout the First World War - it was bond forged of two island peoples, who shared a maritime destiny."

Pure Edward VII.

The Fall of Singapore : The Great Betrayal from Spike EP on Vimeo.

"I regard the attached to be most serious... Here we are, about to be at war with Japan... Here are all these Englishmen - two of whom I know personally - running around, collecting information for the Japanese..."

- Winston Churchill washes his hands

Summer 1941

"Though it's largely forgotten now, Japan had been an ally of Britain throughout the First World War - it was bond forged of two island peoples, who shared a maritime destiny."

Pure Edward VII.

The Strange Deaths of President Harding : Tarpley - Britain's Silent War Against the US from Spike EP on Vimeo.

"The destabilisation of President Harding bears an uncanny similarity to the British-directed Whitewatergate operations against President Clinton..."

Harding was the first US President to visit Canada, specifically British Columbia - one week later he was dead; poisoned.

It was by way of this political succession in the U.S. that Japan was thereby afforded the opportunity to become the pre-eminent military power in the Pacific Rim and achieve Naval Supremacy over the course of the subsequent two decades, 1921-1941.

"Frank Kitson's book will be of special interest to those of us who served in Kenya during the Mau Mau rebellion since few people could be told at the time of the special operations developed by him. But there are many lessons in his story which will be of equal interest to those whose business it is to study or take part in the restoration of law and order. The British Army has been kept busy with that kind of work in recent years.

Global war is an international affair and it is in the international field that our statesmen will strive to reach agreement to reduce the likelihood of such a calamity. But keeping control in our Colonies and Protectorates is our own affair. The likelihood of military support to our Colonial administration must be rated high.

In Africa alone there are vast areas which under our guidance are moving towards a greater degree of self government. We are deliberately moving the responsibility more and more on to the shoulders of the local inhabitants. This involves risks to law and order which must be accepted if these people are to move from the benevolent autocracy of good Colonial administration to independence, with all the dangers, disturbances and upheavals which such a change entails.

If this change is to be made smoothly, with firm foundations laid for the future, the timing must be controlled. The Colonial administration must not be stampeded into making the change because its administration has become so weak it cannot resist. It would be the worst possible service to the people of Africa to give independence against a background of confusion.

If the Army is required to intervene it should try to do so in such a way that it does not prejudice the natural progressive development of the territory. No lasting results will be obtained by the unintelligent use of force in all directions. Measures must be designed to support and protect the loyal members of the community and to round up the real trouble-makers who have resorted to force and lawlessness. If this can be done fairly and justly you will get the support of the waverers and the battle is half won. But to do this you must have a very good intelligence service. You must not be surprised to find that it is inadequate and your first task should be to build up."

General Sir George Erskine G.C.B, K.B.E, D.S.O

The war in Malaya, 1948-60

“The hard core of armed communists in this country are fanatics and must be, and will be, exterminated”. (Sir Gerald Templer, High Commissioner in colonial Malaya)

Between 1948 and 1960 the British military fought what is conventionally called the “emergency” or “counter-insurgency” campaign in Malaya, a British colony until independence in 1957. The declassified files reveal that Britain resorted to very brutal measures in the war, including widespread aerial bombing and the use of a forerunner to modern cluster bombs. Britain also set up a grotesque “resettlement” programme that provided a model for the US’s horrific “strategic hamlet” programmes in Vietnam. It also used chemical agents from which the US may again have drawn lessons in its use of agent orange.

Defending the right of exploitation

British planners’ primary concern was to enable British business to exploit Malayan economic resources. Malaya possessed valuable minerals such as coal, bauxite, tungsten, gold, iron ore, manganese, and, above all, rubber and tin. A Colonial Office report from 1950 noted that Malaya’s rubber and tin mining industries were the biggest dollar earners in the British Commonwealth. Rubber accounted for 75 per cent, and tin 12-15 per cent, of Malaya’s income.

As a result of colonialism, Malaya was effectively owned by European, primarily British, businesses, with British capital behind most Malayan enterprises. Most importantly, 70 per cent of the acreage of rubber estates was owned by European (primarily British) companies, compared to 29 per cent Asian ownership. Malaya was described by one Lord in 1952 as the “greatest material prize in South-East Asia”, mainly due to its rubber and tin. These resources were “very fortunate” for Britain, another Lord declared, since “they have very largely supported the standard of living of the people of this country and the sterling area ever since the war ended”. “What we should do without Malaya, and its earnings in tin and rubber, I do not know”.

The insurgency threatened control over this “material prize”. The Colonial Secretary remarked in 1948 that “it would gravely worsen the whole dollar balance of the Sterling Area if there were serious interference with Malayan exports”. One other member of the House of Lords explained that existing deposits of tin were being “quickly used up” and, owing to rebel activity, “no new areas are being prospected for future working”. The danger was that tin mining would cease in around ten years, he alleged. The situation with rubber was “no less alarming”, with the fall in output “largely due to the direct and indirect effects of communist sabotage”, as it was described.

An influential big-business pressure group called Joint Malayan Interests was warning the Colonial Office of “soft-hearted doctrinaires, with emphasis on early self-government” for the colony. It noted that the insurgency was causing economic losses through direct damage and interruption of work, loss of manpower and falling outputs. It implored the government that “until the fight against banditry has been won there can be no question of any further moves towards self-government”.

The British military was thus despatched in a classic imperial role – largely to protect commercial interests. “In its narrower context”, the Foreign Office observed in a secret file, the “war against bandits is very much a war in defence of [the] rubber industry”.

The roots of the war lay in the failure of the British colonial authorities to guarantee the rights of the Chinese in Malaya, who made up nearly 45 per cent of the population. Britain had traditionally promoted the rights of the Malay community over and above those of the Chinese. Proposals for a new political structure to create a racial equilibrium between the Chinese and Malay communities and remove the latter’s ascendancy over the former, had been defeated by Malays and the ex-colonial Malayan lobby. By 1948 Britain was promoting a new federal constitution that would confirm Malay privileges and consign about 90 per cent of Chinese to non-citizenship. Under this scheme, the High Commissioner would preside over an undemocratic, centralised state where the members of the Executive Council and the Legislative Council were all chosen by him.

At the same time, a series of strikes and general labour unrest, aided by an increasingly powerful trade union movement, was threatening order in the colony. The colonial authorities sought to suppress this unrest, banning some trade unions, imprisoning some of their members and harassing the left-wing press. Thus Britain used the emergency, declared in 1948, not just to defeat the armed insurgency, but also to crack down on workers’ rights. “The emergency regulations and the police action under them have undoubtedly reduced the amount of active resistance to wage reductions and retrenchments”, the Governor of Singapore – part of colonial Malaya – noted. In Singapore, the number of unions “has decreased since the emergency started”. Colonial officials also observed that the curfews imposed by the authorities “have tended to damp down the endeavours of keen trade unionists”. Six months into the emergency the Colonial Office noted that in Singapore “during this period the colony has been almost entirely free from labour troubles”.

Britain had therefore effectively blocked the political path to reform. This meant that the Malayan Communist Party – which was to provide the backbone of the insurgency – either had to accept that its future political role would be very limited, or go to ground and press the British to leave. An insurgent movement was formed out of one that had been trained and armed by Britain to resist the Japanese occupation during the Second World War; the Malayan Chinese had offered the only active resistance to the Japanese invaders.

The insurgents were drawn almost entirely from disaffected Chinese and received considerable support from Chinese “squatters”, who numbered over half a million. In the words of the Foreign Office in 1952: “The vast majority of the poorer Chinese were employed in the tin mines and on the rubber estates and they suffered most from the Japanese occupation of the country… During the Japanese occupation, they were deprived both of their normal employment and of the opportunity to return to their homeland…Large numbers of Chinese were forced out of useful employment and had no alternative but to follow the example of other distressed Chinese, who in small numbers had been obliged to scratch for a living in the jungle clearings even before the war”. These “squatters” were now to be the chief object of Britain’s draconian measures in the colony.

The reality of the war

To combat an insurgent force of around 3,000-6,000, British forces embarked on a brutal war which involved large-scale bombing, dictatorial police measures and the wholesale “resettlement” of hundreds of thousands of people. The High Commissioner in Malaya, Gerald Templer, declared that “the hard core of armed communists in this country are fanatics and must be, and will be, exterminated”. During Templer’s two years in office, “two-thirds of the guerrillas were wiped out”, writes Richard Clutterbuck, a former British official in Malaya, which was a testament to Templer’s “dynamism and leadership”.

Britain conducted 4,500 air strikes in the first five years of the Malayan war. Robert Jackson writes in his uncritical account: “During 1956, some 545,000 lb. of bombs had been dropped on a supposed [guerrilla] encampment…but a lack of accurate pinpoints had nullified the effect. The camp was again attacked at the beginning of May 1957…[dropping] a total of 94,000 lb. of bombs, but because of inaccurate target information this weight of explosive was 250 yards off target. Then, on 15 May…70,000 lb. of bombs were dropped”.

“The attack was entirely successful”, Jackson declares, since “four terrorists were killed”. The author also notes that a 500 lb. nose-fused bomb was employed from August 1948 and had a mean area of effectiveness of 15,000 square feet. “Another very viable weapon” was the 500 lb. fragmentation bomb, a forerunner of cluster bombs. “Since a Sutherland could carry a load of 190, its effect on terrorist morale was considerable”, Jackson states. “Unfortunately, it was not used in great numbers, despite its excellent potential as a harassing weapon”. Perhaps equally unfortunate was a Lincoln bomber, once “dropping its bombs 600 yards short…killing twelve civilians and injuring twenty-six others”. Just one of numerous examples of “collateral damage” from the forgotten past.

Atrocities were committed on both sides and the insurgents often indulged in horrific attacks and murders. A young British officer commented that, in combating the insurgents: “We were shooting people. We were killing them…This was raw savage success. It was butchery. It was horror.”

Running totals of British kills were published and became a source of competition between army units. One British army conscript recalled that “when we had an officer who did come out with us on patrol I realised that he was only interested in one thing: killing as many people as possible”. British forces booby-trapped jungle food stores and secretly supplied self-detonating grenades and bullets to the insurgents to instantly kill the user. SAS squadrons from the racist regime in Rhodesia also served alongside the British, at one point led by Peter Walls, who became head of the Rhodesian army after the unilateral declaration of independence.

Brian Lapping observes in his study of the end of the British empire that there was “some vicious conduct by the British forces, who routinely beat up Chinese squatters when they refused, or possibly were unable, to give information” about the insurgents. There were also cases of bodies of dead guerrillas being exhibited in public. This was good practice, according to the Scotsman newspaper, since “simple-minded peasants are told and come to believe that the communist leaders are invulnerable”.

At Batang Kali in December 1948 the British army slaughtered twenty-four Chinese, before burning the village. The British government initially claimed that the villagers were guerrillas, and then that they were trying to escape, neither of which was true. A Scotland Yard inquiry into the massacre was called off by the Heath government in 1970 and the full details have never been officially investigated.

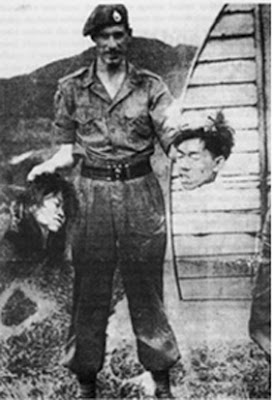

Decapitation of insurgents was a little more unusual – intended as a way of identifying dead guerrillas when it was not possible to bring their corpses in from the jungle. A photograph of a Marine Commando holding two insurgents’ heads caused a public outcry in April 1952. The Colonial Office privately noted that “there is no doubt that under international law a similar case in wartime would be a war crime”. (Britain always denied it was technically at “war” in Malaya, hence use of the term “emergency”).

Dyak headhunters from Borneo worked alongside the British forces. High Commissioner Templer suggested that Dyaks should be used not only for tracking “but in their traditional role as head-hunters”. Templer “thinks it is essential that the practice [decapitation] should continue”, although this would only be necessary “in very rare cases”, the Colonial Office observed. It also noted that, because of the recent outcry over this issue, “it would be well to delay any public statement on this matter for some months”. The Daily Telegraph offered support, commenting that the Dyaks “would be superb fighters in the Malayan jungle, and it would be absurd if uninformed public opinion at home were to oppose their use”. The Colonial Office also warned that, in addition to decapitation, “other practices may have grown up, particularly in units which employ Dyaks, which would provide ugly photographs”.

Templer famously said in Malaya that “the answer lies not in pouring more troops into the jungle, but in the hearts and minds of the people”. Despite this rhetoric, British policy succeeded because it was grossly repressive, and was really about establishing control over the Chinese population. The centrepiece of this was the “Briggs Plan”, begun in 1950 – a “resettlement” programme involving the removal of over half a million Chinese squatters into hundreds of “new villages”. The Colonial Office referred to the policy as “a great piece of social development”.

Lapping describes what the policy meant in reality: “A community of squatters would be surrounded in their huts at dawn, when they were all asleep, forced into lorries and settled in a new village encircled by barbed wire with searchlights round the periphery to prevent movement at night. Before the ‘new villagers’ were let our in the mornings to go to work in the paddy fields, soldiers or police searched them for rice, clothes, weapons or messages. Many complained both that the new villages lacked essential facilities and that they were no more than concentration camps”. In Jackson’s view, however, the new villages were “protected by barbed wire”.

A further gain from “resettlement” was a pool of cheap labour available for employers. Following the required framing, this was described by Clutterbuck as “an unprecedented opportunity for work for the displaced squatters on the rubber estates”. A government newsletter said that an essential aspect of “resettlement” was “to educate [the Chinese] into accepting the control of government” – control over them, that is, by the British and Malays. “We still have a long way to go in conditioning the [Chinese]“, the colonial government declared, “to accept policies which can easily be twisted by the opposition to appear as acts of colonial oppression”. But the task was made easier since “it must always be emphasised that the Chinese mind is schizophrenic and ever subject to the twin stimuli of racialism and self-interest”.

A key British war measure was inflicting “collective punishments” on villages where people were deemed to be aiding the insurgents. At Tanjong Malim in March 1952 Templer imposed a twenty-two-hour house curfew, banned everyone from leaving the village, closed the schools, stopped bus services and reduced the rice rations for 20,000 people. The latter measure prompted the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to write to the Colonial Office noting that the “chronically undernourished Malayan” might not be able to survive as a result. “This measure is bound to result in an increase, not only of sickness but also of deaths, particularly amongst the mothers and very young children”. Some people were fined for leaving their homes to use outside latrines.

In another collective punishment – at Sengei Pelek the following month – measures included a house curfew, a reduction of 40 per cent in the rice ration and the construction of a chain-link fence 22 yards outside the existing barbed wire fence around the town. Official explained that these measures were being imposed upon the 4,000 villagers “for their continually supplying food” to the insurgents and “because they did not give information to the authorities” – surely far worse crimes than decapitation. British detention laws resulted in 34,000 people being held for varying periods in the first eight years of the emergency. The Foreign Office explained that detention regulations covered people “who are a menace to public security but who cannot, because of insufficient evidence, be brought to trial”. Around 15,000 people were deported. The laws that enabled the High Commissioner to do this detainees extended “to certain categories of dependants of the person concerned”. The High Commissioner’s view was that “the removal of all the detainees to China would contribute more than any other single factor to the disruption” of the insurgency.

Jackson comments: “Templer’s methods were certainly unorthodox but there was no doubt that they produced results”. Richard Allen, in another study, agrees, noting that “one obvious justification of the Templer methods and measures…is that the course he set was maintained after his departure and achieved in the end virtually complete success”. The ends justify the means. Many British policies in the Malayan war were copied with even more devastating effect by the US in Vietnam. “Resettlement” became the “strategic hamlet” programme. Chemical agents were used by the British in Malaya for similar purposes as agent orange in Vietnam. Britain had experimented with the use of chemicals as defoliants and crop destroyers from the early 1950s. From June to October 1952, for example, 1,250 acres of roadside vegetation at possible ambush points were sprayed with defoliant, described as a policy of “national importance”. The chemicals giant ICI saw it, according to the Colonial Office, as “a lucrative field for experiment”. I could find nothing further on this programme in the declassified files.

The convenient pretext

As noted above, the war was essentially fought to defend commercial interests. It was not that British planners believed there was no “communist” threat at all – they did. But the nature of this threat needs to be understood. Communism in Malaya – as elsewhere in the Third World during the cold war – primarily threatened British and Western control over economic resources. There was never any question of military intervention in Malaya by either the USSR or China, nor did they provide any material support to the insurgents: “No operational links have been established as existing”, the Colonial Office reported four years after the beginning of the war. Rather, the British feared that the Chinese revolution of 1949 might be repeated in Malaya. And as the Economist described, the significance of this was that communists “are moving towards an economy and a type of trade in which there will be no place for the foreign manufacturer, the foreign banker or the foreign trader” – not strictly true, but a view that conveys the threat that the wrong kind of development poses to the West’s commercial interests.

British policy – then and now – cannot be presented as being based on furthering such crude aims as business interests. So the official pretext became that of resisting communist expansion, a concept shorn of any commercial motives and simply understood as defending the “free world” against nasty totalitarians. Academics and journalists have overwhelmingly fallen into line with the result that the British public have been deprived of the realistic picture.

Let us take a couple of examples of how the required doctrine has been promoted. One of the most reputed analysts of early postwar British foreign policy, Ritchie Ovendale, asserts that Britain was “fighting the communist terrorists to enable Malaya to become independent and help itself”. Motives of straightforward commercial exploitation do not figure at all in Ovendale’s account. Later, he only quickly mentions that Britain is “dependent on the area for rubber, tea and jute” and that “the economic ties could not be severed without serious consequences”. Ovendale writes that Britain’s long term objective in Southeast Asia was “to improve economic and social conditions” there. How this is compatible with Britain’s ciphoning off profits from Malayan rubber and tin exports at the expense of the poverty-stricken population is left unexplained. Overall, Ovendale contends, Britain’s “immediate intention” in the region was to “prevent the spread of communism and to resist Russian expansion”.

An equally disciplined approach is by Robert Jackson who, in a book-length study of the war, also makes no mention of Britain’s exploitation of rubber and tin resources for British purposes. Again, Britain was simply resisting communist expansion. “Even by April 1950, the extent of the communist threat to Malaya was not fully appreciated by the British government”, Jackson comments. Things changed, he claims, with the election of Churchill as Prime Minister in 195l: “Churchill’s shrewd instinct grasped the fact that if Malaya fell under communist domination, the rest of Asia would quickly follow”. Note how this contention, often repeated in the declassified files, is presented as a “fact”.

Other aspects of the war are dealt with within the official framework. In 1952 a memorandum by the British Defence Secretary stipulated that, from now on, the insurgents – previously usually referred to as “bandits” – would be officially known as “communist terrorists” or CTs. Subsequent scholarship concurred. Richard Allen contrasts the “CTs…as they came to be known” with the Malay and British security forces, the “defenders of Malaya”, in his term.

Former Sunday Times correspondent James Adams notes in his book that since Malaya was a British colony “responsibility for the conduct of the war fell to the British government”. Saying that Malaya – subjugated by Britain for its own economic ends – was a British “responsibility” is perhaps like saying that the former East Germany was a Soviet “responsibility”.

Britain achieved its main aims in Malaya: the insurgents were defeated and, with independence in 1957, British business interests were essentially preserved. Britain handed over formal power at independence to the traditional Malay rulers and fostered a political alliance between the United Malay National Organisation and the Chinese businessman’s Malayan Chinese Association. At independence, 85 per cent of Malayan export earnings still derived from tin and rubber. Around 70 per cent of company profits were in foreign, mainly British, hands and were largely repatriated. Largely European owned agency houses controlled 70 per cent of foreign trade and 75 per cent of plantations. Independence hardly changed the extent of foreign control over the economy until the 1960s and 1970s. Even by 1971, 80 per cent of mining, 62 per cent of manufacturing and 58 per cent of construction were foreign-owned, mainly by British companies. The established order had been protected.