Some of the information provided in the e-mail posting has been independently verified by EIR. Indeed, three MI6 officials, identified as having been intimately involved in the events leading up to the fatal crash, and the ensuing cover-up, have been previously identified by EIR as suspected culprits, acting on behalf of the House of Windsor, under the personal orders of Prince Philip.

In the interest of furthering the investigation into the Paris crash, we publish the text of the anonymous document below. We cannot, at this time, independently authenticate many of the details provided.

However, we pass the document along as "raw" material. As we pursue the leads contained in the document, we will keep our readers informed.

Here is the e-mail text (the names section contains the year and city to which the alleged agents were posted):

Professor Pritchard of Gonville and Cauis College Cambridge is the leading recruiter for MI6 agents. He identifies and recruits the most intellectual geniuses for MI6.

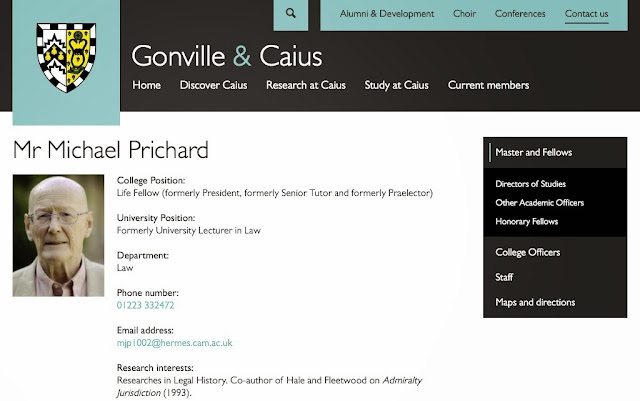

Mr Michael J Prichard

By Lesley Dingle and Daniel Bates

Michael J. Prichard: Life Fellow of Gonville & Caius- 1927: Born 27 November 1927 in Banstead, Surrey

- 1933-45: Wimbledon College

- 1945-48: Kings College London

- 1948 -50: Queens’ Cambridge, LLB 21-23 yrs old

- 1950-1995-2012: Teaching Fellowship-Life Fellow at Gonville & Caius (President, Senior Tutor and Praelector),

- 1951: University Lecturer (originally assistant)

- 1952-53: Practised in Chancery Division

- 1962-65, 1966-69: Secretary to Faculty

- 1964: Council of Selden Society

- 1976-80: President of Gonville & Caius

- 1980-88: Senior Tutor of Gonville & Caius

- 1995 Retired from University Lectureship

- 1996-2001: Chambers - the Bromfield & Yale arbitration

- 1996- 2002: Editor of Cambridge Law Journal

- 2008-2010: Waterhouse Gate Project

The War and immediate aftermath

Born in 1927, Michael J Prichard was almost twelve years old when war broke out in September 1939, and by its end, two of his elder brothers were serving in the armed forces: Hugh in the Territorials and Alan in the Royal Navy. The family lived at Sutton (Surrey), near to where Michael had been born in Banstead, and this entailed a long daily commute by bus to school at Wimbledon College, a Jesuit establishment which he attended from before the war and until 1945. Neither the school nor the family were evacuated, so this routine continued throughout the Blitz and subsequent raids, and Mr Prichard’s memories of the time are remarkably prosaic - " I vividly remember we would travel over in the bus and, occasionally, the bus would stop, and we would all have to get out and go for the nearest shelter. That was in the early years, when the bombings were. Nothing came very close to us. Sutton was very close to Croydon Aerodrome1." And "the school didn’t get hit at all, because we weren’t in the East End....It was much more at night when it was over the whole of the city, but we were still on the suburbs. I don’t want to over dramatise it, but there were one or two [bombs] fairly close. Put it this way, near enough at home to blow out the windows of the houses....so, my brothers and I tended to spend our evenings going round houses replacing panes of glass".The local destruction caused by bombing, as well as the mayhem on a global scale, did not appear to have had any marked emotional effects on Michael, and in answer to a specific question - "I don’t think so. No. I think we were fairly young, so it was all very exciting and I know that sounds [strange] nowadays, but you know, as boys, one would plot the flow and the fall back of the German troops in Russia. So, one learned a good deal of geography". As he remarked, however, he did have two brothers in the forces by 1945, and this posed one source of constant worry for the family.

Nevertheless, there were practical deprivations, and at school emphasis was on classes that required little equipment. For instance, chemistry was a subject that suffered because chemicals were hard to come by during the war, while physics was taught from a mathematical standpoint. For Michael this was no great loss, as the classics, history and languages (French and Latin) were his forte, but he remembers there were difficulties in replacing exercise books. Meanwhile, life at home was frugal, but he implied that, in comparison to today, people "were healthier during the war: we had fairly sparse rations."

By coincidence, he left school in 1945 as the war ended, and because the armed forces were rapidly scaling down, he avoided being called-up. At this crucial point, as Michael put it, "luckily" his father managed to arrange for his entrance to the local university, King’s College, London, where he decided to read law. Later, two of his brothers followed him to Kings, where they both also did law: Brian became a solicitor and senior partner in a London law firm, and Alan, Professor of Law at Nottingham University.

The legacy of war had other, more nuanced, influences on Mr Prichard’s career, however, and these resulted from a combination of two factors. Firstly the physical destruction of parts of London and its infrastructure from German bombing, and secondly, the fact that many academics had been called into the armed forces, so that the sizes of departments’ staffs in the immediate post-armistice period were very small.

King’s College is in central London, and occupied the east wing of Somerset House, which then also housed The Admiralty, Inland Revenue and the Registrar General of Births Deaths and Marriages. Somerset House was extensively damaged by bombing (the college had relocated to Bristol for the duration of the war) and in late 1945 law facilities were poor and lectures were crammed into one small room. Other law faculties in the London University system were in similar straitened circumstances, which, coupled with lack of staff meant that courses at King’s College in the 1945-48 period were shared with the London School of Economics (less than 1/2 mile to the north, and only recently returned to London from Peterhouse College, Cambridge), and University College in Gower Street (~1 mile away, also badly damaged). The latter was amusingly referred to by Mr Prichard and his fellow King’s students as the "Godless Institution", a reference to its secular origins, in contrast to King’s College’s Anglican roots2.

Shuttling back and forth for their classes between these three centres, in a city only slowly recovering from massive destruction and dislocation, posed all manner of logistical problems to Michael and his fellow students. Nevertheless, this awkward arrangement had one priceless advantage - the students had access to a wider than normal spectrum of scholars, and by good fortune, this included some luminaries whose profound influence Mr Prichard acknowledges to this day. Three stand out above the others: Harold Potter 3(King’s: his passion for the law and his exciting lectures), Glanville Williams 4(LSE: his lectures were very precise and clearly expounded) and Herbert Jolowicz5 (UCL: an exceptional lecturer who taught MJP "all the Roman Law I ever knew").

Potter in particular was crucially influential, as it was he who steered Michael to Gray’s Inn (where he obtained a fellowship), and later, through his friendship with Professor Emlyn Wade, helped Michael proceed on to Queens’ College, having engineered a King’s post-graduate scholarship that he could hold at Cambridge. There was also the critical presence at King’s of Albert Kiralfy, who, as we shall see later, made valuable contributions to particular career-long research topics for Michael.

Escape to Cambridge

Thus, in the autumn of 1948, Michael Prichard found himself beside the Cam in a dramatically contrasting environment to the hectic, disrupted life of the capital. Even the days seemed longer - there being three hours extra for study now that he had no commute on overburdened bus and underground systems to contend with. The latter had curtailed the working days in London for students and faculty, alike, while reducing time for study in the library to a minimum. Michael’s bus journey into town every day had taken at least an hour and a half, so that lectures never started before 10am, while the days had finished at 3.30-4.00 pm so that people could make their way home. In fact, the logistics had imposed themselves on the teaching methods that were employed in London, and Michael said that details of many cases had to be taken on trust, there being little opportunity to follow things up in the library. Luckily, lecturers such as Herbert Jolowicz and Glanville Williams had gone to great pains to make their presentations as comprehensive as possible, knowing the limits of time and resources under which their students laboured. At Queens’ he could study in the Squire Law library until 7.00 pm and then walk leisurely back to hall. Different worlds.There was one important similarity, however, between his time at London and his early years at Cambridge, particularly at Queens’ College: the phenomenon of the "returning warriors". In previous interviews for the Archive this had been a feature in the reminiscences of other of our eminent scholars of Mr Prichard ’s vintage, and it involved both staff and students. Faced with a flood of demobilised young men and women (the latter thin on the ground at Cambridge colleges), and an impending employment problem, many went to universities to complete their education. These were young people, but emotionally mature, with broad views of the world and in many cases, already used to considerable responsibility.

Queens’ in 1948 was "completely full of people from all sorts of different backgrounds" and for those years there was no class-distinction. As Mr Prichard put it, "a day school boy" never "had the slightest feeling that one was a working class boy, or something". He remembers these colleagues for their pragmatism in degree expectations, and their being "far less demanding....they didn’t want to be spoon fed....and did not expect everything to be laid on a plate". This was partly explained by the Bar in those days not expecting firsts or two-ones, so there was much less examination pressure than at present.

Staff numbers were still relatively small, even at Cambridge, and the Faculty was run by a mixture of staff primarily too old for service, along with a few who had returned already from the war. Later in the interviews, Mr Prichard referred to the former as "the old guard" and the latter as "young Turks" because they came back fired up to resume their careers in a significantly changed society. The "old guard", who were primarily World War One veterans, included such luminaries as Harry Hollond6, Hersch Lauterpacht7, Patrick Duff8, Emlyn Wade9, and Percy Winfield10 (who had already retired), while the returning warriors, the "young Turks", included Robbie Jennings11, T. Ellis Lewis12, Bill Wade13, Arthur Armitage14, Dick Gooderson15, John Thornely16, Micky Dias17, John Hopkins18, Jack Hamson19 and David Williams20. Of course, there was also the ever-faithful Dr Kurt Lipstein1who, after his early internment for being a German pre-war immigrant, had acted as Faculty Secretary and night warden on the Old Schools roof throughout the war, and who was instrumental in organizing Michael a Squire Scholarship of £60 p.a. that allowed him to make ends meet during his time at Queens’.

At Queens’, Michael enrolled for the LLB. This was a two year course, and in the first year he read Legal History, Administrative Law, and Comparative English and Roman Law. He recalled that although one of the outstanding characteristics of a Cambridge education was (and is) the system of supervisions, there were none at that time at Queens’ in the LLB. This was because of staff shortages, so that students were very much left to their own devices. He took the examination at the end of his first year, and recalls that in those days the format was much more flexible than now: "... answer up to four questions but, whether you answered one or four, was entirely left to you and I do remember, in one of the legal history papers, I spent the whole three hours writing on Action on the Case."

The second year (1949-50) he spent on research, and his verdict on his new milieu was "those were very good days at Queens’, those two years", and they were made all the more so by his three fellow-students (Bill Wedderburn22, David Widdicombe23 and Newey24) and their mentor Arthur Armitage. They would meet in Armitage’s rooms for discussions in an atmosphere that was both interesting and "great fun".

The oases of G&C and the Old Schools

It is not surprising that Mr Prichard should want to prolong his stay in such conducive academic environments, and before ending his second year at Queens’, he had organised a Fellowship at Gonville & Caius starting in late 1950. His stay was to stretch for over six decades, and is still not at an end.Professors Emlyn Wade and Arnold McNair (already retired), were Caius Fellows and took Michael’s well-being to heart, to the extent that they persuaded the college to let him gain practical legal experience. He was already a member of the Bar (Gray’s Inn) and they generously allowed him to take a whole year in chambers. He was under the disabled, but brilliant, counsel John Brunyate whose offices were at No. 4 Stone Buildings, close to Chancery Lane tube station. Michael described Brunyate as "the great intellectual in the Chancery Division", who had been a prize fellow at Trinity, and whose speciality was the law relating to charities25. This was another very happy time for Michael, when he enjoyed the intellectual discussions at afternoon tea, and was able to commute during the week to his parents’ home across town in Epsom. He enjoyed the life at the Bar, and at the end of his year (1952-3) found that they were "quite keen to keep me", but by then he had already been given a university assistant lectureship (in 1951), and his involvement with academia was too strong a bond to break.

Despite his day-job at Stone Buildings, he had not been let off his teaching duties at college, and had to return every weekend to Cambridge to undertake twelve hours of supervisions. This was a tough schedule, but as he pointed out, in the early fifties most university teachers lectured on Saturday mornings. So, for a year, although technically a staff member, Mr Prichard became one of the legendary Cambridge "weekenders", a phenomenon necessitated by staff shortages and the wave of war-service returnees. These part-timers sustained and enriched teaching during the post-war years.

Once permanently back at Caius after his stint in chambers, Mr Prichard , as a junior staff member, had himself to rely on weekenders to keep teaching on schedule. With pressure on staff, one had to turn one’s hand to whatever tasks the Faculty Chairman and Secretary allocated, and Michael and other younger members, such as John Thornley and Micky Dias, both of whom had come back after the war, had to teach unfamiliar topics, or persuade weekenders to do them. It was during his teaching of Roman Law to the LLBs that the notes he had taken during the meticulous first year lectures by Herbert Jolowicz at UCL saved the day.

The Faculty evolves

One fascinating aspect of Mr Prichard’s reminiscences is that they record the unbroken evolution of the Faculty as a community over the long period from 1950 to the 1990s. It is worth summarising this, as few others living, and none of the previous Eminent Scholars interviewees (with the exception of the late Mr Mickey Dias) were ever-present in the Faculty over this time. The whole of this period coincided with the Faculty’s occupation of the Old Schools buildings in the city centre: the move to the present Sidgwick site occurred in 1995, the year that Michael Prichard retired.In the fifties Mr Prichard remembers with fondness the relatively small, tightly-knit Faculty which occupied the Old Schools site, immediately west of Senate Passage. This consisted of a quadrangle of various renovated mediaeval/Tudor/18th century buildings around the Cobble Court, flanked to the north by the Victorian Cockerell Building. Law shared this space with the university Administration and the History department Seeley Library, which was on the ground floor of the Cockerall Building - the Squire Law Library was upstairs. Lectures were given in what had been the School of Canon Law (room 4) and the School of Civil Law (room 3). Only Dr Kurt Lipstein (room 5) and the Whewell Professor Hersch Lauterpacht (room 6) had their own very small rooms off the Squire Library, and the social heart of the Faculty was a small tea room (Lecturer’s Combination Room) in the south wing26. What created such a positive environment was the willingness of faculty members to congregate for tea at 11 o’clock by coming across from their far-flung colleges or staying after they had completed their lectures. The atmosphere was especially dependant on the presence of the previously-mentioned "young Turks", whom Mr Prichard described as the "powerhouse, the engine room of the Faculty", and who bolstered the "old guard". It was at tea time that he and the other assistant lecturers (e.g. Thornley and Mickey Dias) would haggle over their teaching loads, and it was there that "really most of the Faculty business was done. One would talk about the latest case arguments, and visitors to the Faculty would come too." He was particularly grateful for opportunities to discuss topics with live-wires such as Bill Wedderburn, while the conscientious appearance at 11 o’clock for discussions with his students by Professor Lauterpacht, and the ever-present Dr Lipstein, gave the library an air of purpose and scholarship.

Tea was taken downstairs and was made in an "enormous great pot by the lady cleaner"who was one of only five people effectively maintaining the physical necessities of the Faculty and Library. T Ellis Lewis was the librarian27, with Clarence Staines28 and Teddy Hill29 his assistants. Secretarial duties were undertaken by "Betty" Suckling30 who worked with her little dog in a small office. The library staff was bolstered on 1st January 1959 by the arrival of W. A. F. P. "Willi" Steiner31 as Assistant Librarian, who, during his time at the library, devised a new cataloguing system for the continually expanding collection.

In those days, the daily teaching schedule was relatively fixed, with lectures starting at 9 o’clock and going on all morning; 2 - 5pm was allocated for sport, and 5 - 7pm for supervisions. This gave cohesion to Faculty activities which were focussed around the lecture rooms, the Squire Library and the tea-room.

The 50s were the heydays of the weekenders. Saturday morning lectures were de rigeur, being the only times when busy practicing lawyers, who were crucial to supplement the sparse staff complement and burgeoning student numbers, both legacies of the war, could give of their time. Some weekenders travelled from afar - Mr Prichard mentioned how, when Scots Law was taught, Ashton-Cross32would come down from Scotland every Friday evening to take courses. Apart from providing the weekenders with a welcome supplement to their salaries, Mr Prichard prides himself on knowing that at Gonville & Caius, Arnold McNair and Emlyn Wade always welcomed weekenders with accommodation and dining rights at High Table. Some of these went on to prominence: "It’s always been a pleasure to know that one of my earliest weekend supervisors was later the Chief Justice, Lord Lane33. Geoffrey Lane had been demobbed after a very outstanding career in the RAF". Also, " Arnold’s nephew came up to do the International Law and of course we got a lot of Caians who could always produce international lawyers, because the legal advisors to the Foreign Office tended all to be McNair’s disciples. By that time [he was a ] world famous international lawyer."

But all complex social arrangements evolve, and as the legacies of the wartime disruption faded, Mr Prichard recalled that the Faculty cohesion centred on the Old Schools began to break down as the nineteen sixties progressed. This was a result of various unrelated factors, which he observed from the vantage point of being Secretary of the Faculty Board, a position he occupied for a total of six years in two separate stints (1962-65, 1966-69). He claimed this as a record, with a mixture of both pride and some regret.

His first term as Secretary coincided with the Faculty Chairmanships of Armitage and Jennings, whom he found excellent to work with, but he admitted that without the help of some meticulous notes of precisely what to do during every full week of term, compiled during previous tenures by John Thornley (1957-59) and Mickey Dias (1969-62), he would have found the job impossible. A crucial part of his responsibility was, with the Chairman, to organise the lecture timetable. Significantly, recent government legislation had made the Secretary’s task considerably more onerous by their now being responsible for completing annual tax returns for all staff members, as well as for paying their salary cheques. As a result, Faculty and the university recognised that the Secretary now needed extra support.

Michael gratefully relinquished the post and took a year’s sabbatical (1965-66), only to find himself prevailed upon a year later when Mr Tony Jolowicz gave up the Secretaryship after just one year. It was this second spell that Mr Prichard felt was so frustrating. Much of the time was spent training the "very charming Colonel Farrow", whom the Faculty had appointed as the new full-time professional help, but for various reasons, the arrangement was not a success. Also, other, more fundamental, problems were beginning to afflict the Faculty and its smooth operation. At their heart was the desire of the University Administration to oust the Law Faculty from its rooms in the Old Schools after their own attempt to acquire the Old Addenbrookes Site on Trumpington Street (now occupied by the Judge Business School) had failed. Mr Prichard remembers he and Glanville Williams (Chairman) spending many days carefully measuring every room in the Old Schools as a possible prelude to rehousing Criminology - but to no avail. Administration stayed, and there began a long war of attrition, fought by successive Secretaries and Chairmen.

The first setback came in 1968. On a false premise, the Faculty relinquished the old School of Civil Law (Room 3), with its grand Regius Professor’s throne, and solid oak lecture benches that had been put in before WWII. Despite the promise of this being a "temporary" arrangement, Room 3 was lost for ever and the Administration installed computer rooms and staff. The Faculty also lost Room 4 (the old School of Canon Law), and although it received the East Room (on the east side of the Cobble Court) in compensation, the ensuing disruption meant that lectures had to be fitted in elsewhere. Clive Parry took over the Chairmanship from Glanville Williams (when he was appointed Rouse Ball Professor) in 1968, and Mr Prichard remembers the contrast between the " very patient, reserved....very quiet" manner in which Williams had dealt with the irritations of the Administration’s designs on the Old Schools, and the "quite firm" views that Parry had "about the relative importance of the Law School, the Old Schools and the Administration." Both approaches were doomed to failure.

A further major development in 1968 was the moving out of the History Department Seeley Library, so that the Squire Law Library expanded into the ground floor of the Cockerell Building. This coincided with a major turnover in the Squire Library staff: Willi Steiner and Clarence Staines retired after 18 and 37 years service, respectively, while William T. Major became Librarian in the same year, replacing the indomitable T E Lewis (37 years service). Peter Zawada34 arrived in 1969. These upheavals, with which Mr Prichard, as Secretary, had to cope, were compounded during 1968 by a local manifestation of the world-wide student unrest35, with a sit-in in the recently acquired East Room This resulted in considerable damage and much upheaval, and according to Mr Prichard "effectively ruined the room". These combined events disrupted the lecturing timetable and weakened the community ethos still further. Fewer Faculty members congregated for the 11am tea break downstairs, and reinforced a trend that begun in the mid-60s with a rival attraction upstairs in the Regent House Combination Room (mid-way between Seeley and Squire library levels) - coffee. It was a trend that became progressively more marked in the 70s and 80s.

Mr Prichard’s marathon stint as Secretary to the Faculty Board came to an end in 1969, and he retreated to Gonville & Caius, from the shelter of which he observed the increasingly disrupted machinations of the Faculty.

By the 70s, the "Young Turks", who had been so instrumental in reviving the Faculty’s fortunes in the 50s, had matured into senior citizens, and a new generation had arrived. Also student numbers had grown, so that larger teaching venues were required and lectures had to be held wherever room was available, particularly in the colleges. Consequently, fewer people were lecturing during the late morning, and teatime all but ceased to be an occasion for congregating and discussion. This was partly because the "younger generation were not willing to put up with the rather stewed tea with which they were confronted when they arrived at ten past eleven", and they went upstairs for coffee, leaving only older members downstairs. But it was mainly because staff were elsewhere at that time. With more and more lectures being given in the afternoons, morning supervisions were now common, and the traditional timetable was largely abandoned.

Mr Prichard ’s withdrawal from administrative duties in the faculty, allowed him to concentrate on college activities at Caius, and, for a few years, on his own research interests, which had suffered during the sixties because of Faculty commitments. His administrative chores, however, once again proved a handicap to pressing ahead with his projects, and he took on the Presidency of Gonville & Caius in 1976 (to 1980). (This coincided with the early Mastership of Professor William Wade36 1976-88, who had just arrived from Oxford). In itself, the Presidency would not have been too onerous, but it coincided with an administrative impasse that had arisen with the production of the next volume in the biographical history of the college37. The task of updating, started several years earlier by Professor Skemp38, had foundered because the index system was found to be severely wanting. Mr Prichard gamely undertook to sort it out, but in all it devoured nearly four years of valuable research time.

These were early days in the new art of personal computing, and Mr Prichard soon realised that the only solution to avoid compounding the administrative chaos, was to computerise the college biographic records. He single-mindedly set out to devise a system to achieve this in what was to be a long haul for a self-taught archivist. On reflection during our interviews, he called it "madness". Nevertheless, in 1978 the results were published as a 577 page biographic tome that brought up to date the record of college membership from 1349 (Prichard.& Skemp 1978).

His success was such that when his Presidency ended in 1980, he was persuaded to take on the job as college Senior Tutor (1980-88), because by this stage, it was clear to everyone that the college records as a whole, and particularly the tutorial records, also needed to be computerised. Michael Prichard de facto became the resident computer "expert"with the responsibility of bringing the college into the digital age. He recalls that Professor Bill Wade was very supportive of this task, which was undertaken long before the omnipresence of Microsoft, and it entailed a lot of program writing. As is the nature of these things, however, all his efforts are now all "old hat" and completely forgotten. Mr Prichard’s 70s and early 80s were, consequently, consumed by college administration of one sort or another.

There was to be no let up, however, and his prowess in computing was to cost him the rest of the decade. This time the Faculty prevailed upon his hard-earned expertise, and he was asked to computerise the tedious and time-consuming processing of collating the Tripos examination results. Up to this point, the Faculty had relied on a "wonderful system" devised by the late Harry Hollond, but it was labour-intensive and open to error. Mr Prichard found that once his system was up and running, with his team of three assistants (Julie Boucher39, Linda Kernow and Caroline Forsell, the secretary, who by now had replaced Betty Suckling and her dog), he was able to achieve in half a day, what eight people had previously taken at least two full days to complete. Thus armed, the Law Faculty prided itself that it could produce the exam results faster and more accurately than any other faculty.

All this was completed during a further period of further Faculty disruption. By the late 80s the University Administration had finally managed to push the Faculty administrators out of the Old Schools (though the Squire Library was still in place), so that the main office was now located in the Old Syndics Building next to the Pitt Press in Mill Lane. Even some lectures had to be taken in this venue. Mr Prichard recalled that in his capacity of Chairman of the Examining Board, he spent much time to-ing and fro-ing between the Caius and the Old Syndics site.

Research

Mr Prichard devoted much of his career to the Faculty and his college, but it must not be forgotten that he made valuable contributions to scholarship as a legal historian in two main areas: extra-territorial jurisdictions (and in particular Admiralty Law), and an understanding of the development of the notion of negligence in the law of tort. An account of this aspect of his career has been documented separately, but both started while he was a young lecturer at Caius, and that he endured many frustrations and hurdles over the years as pressing administrative duties, which we have already described, successively claimed his attention.His earliest research into extra-territorial jurisdictions occurred in the early 1950s, when he became interested in military law vis a vis common criminal law in R v Page40, which involved murder by a serving British soldier in Egypt and the recently passed Courts-Marshall (Appeals) Act 1951. This military theme was extended when he became involved with David Yale41 in 1960 in a project that spanned over thirty years and resulted in their joint volume Hale and Fleetwood on admiralty jurisdiction42. This was originally conceived to mark the 800th anniversary of the adoption of the Laws of Oléron43, and was to have given account of the history of the Court of Admiralty, but they were thwarted by the sheer volume of data accumulated and it was eventually trimmed to a mere 572 pages in presenting two mediaeval treatises!

Mr Prichard’s second interest, and the one that gave him greatest satisfaction, was the result of tea-room discussions with one of his mentors, Glanville Williams in the early 60s: the practical reasons of when and why to plead the action on the case. He followed this up by researching the case of Williams v Holland (1833), the results of which he published in 196444, and later traced the emergence of the notion of negligence in tort to the eighteen century case (Scott V. Shepherd45) on which he gave the 1973 Selden Society Lecture46.

Retirement

Mr Prichard retired from his University post in 1995, but his contribution to his college and the Faculty have hardly diminished. In chronological order, his post-retirement activities have been: Editor of Cambridge Law Journal and a simultaneous return to chambers at Stone Buildings; the Waterhouse Gate Project at Gonville and Caius; and currently his translating the 1557 statutes of the college.His first assignment was, appropriately, one in which his familiarity with computing and digital technology was to be a tremendous boon. In 1996 he took over the editorship of theCambridge Law Journal (which has been published by Cambridge University Press since 1967) from Colin Turpin47, who had run the operation from his rooms in Clare College. Michael remained in post for six years, and very much enjoyed his editorial work, over the years becoming friendly with many of the authors, "without actually meeting them" by corresponding and occasionally speaking on the phone.

His early years were somewhat disrupted by a major Faculty translocation. In 1987 the Faculty had decided that a new building was necessary, and after years of planning, fund raising and building, it moved to new accommodation in the ultra-modern Sidgwick site in 1996. The CLJ was allocated an office, so Mr Prichard decided to follow in the Faculty’s wake. This involved much re-organisation of records and files from Clare, but his presence in the new building had the advantage that there were now always colleagues on hand to whom he could turn for advice. In particular, he fondly remembers the generous and ever-willing assistance from Emeritus Professor Kurt Lipstein, who had his new office on the third floor: "I could always tackle him when any particular article referred to some abstruse continental case."

This physical upheaval was simultaneously compounded by advances in computing technology that were affecting both commerce and private activities on a global scale, and Mr Prichard soon found that the editorial processes at CLJ were not immune. Luckily he had already embraced such techniques for other tasks, and quickly adapted to electronic editing, filing and having to send manuscripts on disk. E-mailing material was still a few years away, though by the time he gave up the editorship, this era had also arrived. A point he emphasised was that over his tenure at the CLJ the tempo of the editorial operation completely changed - it started in an era when physical copy could take three weeks or more to journey to Australasia and back by airmail, to a time when the turnaround for corrections and queries could be measured in a few days, or even hours. He compared this electronic publishing revolution to that he had shepherded in when computerising the marking of Faculty Tripos examinations a few years earlier.

These first years of retirement were complicated by the fact that Mr Prichard’s tenure as editor of the Cambridge Law Journal, ran in parallel with a second stint of work in chambers near Chancery Lane. Forty five years after his first period in the Stone Buildings he was asked by a former pupil to help on a case that demanded familiarity with documents of the same vintage as those he had studied during his research on the Admiralty Courts. Although all his previous colleagues had since departed from Stone Buildings, Mr Prichard recalls the excitement of returning to his old haunts and reviving reminiscences of his wonderful relationship with the erudite John Brunyate. "[It] was enormous fun", but the nearly five years of a daily commute and having to "fight for a place" on crowded trains was very tiring. The work itself was fascinating, and entailed interpreting a grant dating from 1635 setting out mineral rights on estates in North Wales. A dispute over these rights had been "rumbling on for centuries" and involved the Crown and the estates of the Lordship of Bromfield and Yale48. By coincidence, Mr Prichard’s old friend and colleague on the Admiralty project, David Yale, was related to the Yales in the case, his family having moved from the area to Snowdonia a century earlier, so Michael was able to renew their ties when he and his wife visited North Wales to inspect the great map that the plaintiff kept of the mineral deposits thereabouts that formed the subject of the case.

In the end, it was settled by arbitration in the Middle Temple before a retired judge of the Appeal Court who was suitably proficient in understanding the seventeenth century Latin text of the documents. Mr Prichard recalled that despite his two periods working in chambers, this was as close as he came to appearing in court during his career.

The latter years of Michael Prichard’s retirement have been spent in further services to his college, Gonville and Caius.

The first of these projects involved a piece of historical detective work that Mr Prichard likened to the approach employed by Professor Toby Milsom during some of his legal history endeavours "not so much the effect of it, but what was in the mind". The subject of all this cryptology was what was known at the "Gate of Pride" or "Great Gate" that lies at the foot of the Tower on the King’s Parade frontage of the college, and specifically what the architect, Alfred Waterhouse49, had originally placed at the entrance when the Tower was completed in 1868-70. The reason for this activity arose from a proposal by some Caius Fellows to find a suitable location at which to erect a memorial to the achievements of the late Nobel Laureate Francis Crick50 who was an Honorary Fellow, on the centenary of his birth in 2016. The Great Gate, at the time (2008) a "dark and gloomy....dreadful place....like a coal hole", was being used as a storage area, but Mr Prichard thought that if unblocked and restored to its original form, it was a potential candidate. The problem was, there was little documentary or photographic evidence for what the architect had originally placed at the outer entrance, which was key to converting it to a light and airy passage. Michael therefore had to look into the mind of Alfred Waterhouse - how would he have envisaged it? - hence the analogy with Milsom’s mediaeval judiciary.

The project involved tracking down various college documents, searching through the earliest photographic archives created by Francis Frith51, and rummaging in unlikely corners for discarded iron work. Eventually the original design was deciphered, and in 2010 restored, so that plans for the Crick memorial in the area of the Great Gate are still viable after a period of uncertainty. In the meantime, Mr Prichard’s contribution to refurbishing the gate to its former glory, has been recognised by the insertion of a brass plaque on the wall to the left (west) side of the passage way52. His role in honouring the illustrious scientist is particularly apt, as Michael clearly remembers Crick in the time before and after his and Watson’s53 discovery of the structure of DNA in those heady days in February 1953. His recollections of Crick and his ebullient personality, at a time when he (Michael) was a junior Fellow, are historically symbolic as we approach the Crick centenary.

For his current (2012) project, Mr Prichard is involved in another college centenary - in this case the quincentenary of the birth of John Caius54, who refounded Gonville and Caius in 1557. Caius was born in 1510, so they are running a few years late, but the historical significance of this work extends beyond Cambridge. Unlike most Oxbridge college founders, Caius had personally been a Fellow at the original Gonville Hall55, and he was particularly aware of the pitfalls to be avoided when he provided funds for refounding and financially restructuring the institution. The funds were all based on land. This attention to detail was especially important as it was a time of high inflation and financial instability, following the dissolution of the monasteries (1536-41) by Henry VIII. Caius’ statutes were dated 1573, and are considerably more extensive than for any other Oxbridge college, and contain "very precise statutory instructions about what terms must be imposed upon the sees of land". All this land had been originally copyhold tenure56, a subject that Mr Prichard called "dead learning", and necessitating a great deal of research into English land law.

Mr Prichard has been asked to make a translation of, and to edit and correct the original sixteenth century Latin documents, which had never been properly undertaken previously. He is also writing a commentary based on the surviving college documents, which has involved familiarising himself with a new subject - economic history. He now greatly regrets not having recourse to his early mentor John Brunyate, who was, in his day, a master in the law relating to charities (which all the colleges are).

As he had found so many times in the past, Michael has expended far more effort on the project than anticipated - "[It’s] kept me hopelessly busy....it really is taking far too much of my time and too many other things are having to be put aside and falling behind". It is ongoing, a work in progress, and at the end of our final interview, he said that he was back off to college to continue it.

One can be sure that Michael Prichard will see the project through and produce a meticulous report that will be a fitting tribute to the memory of John Caius’ legacy.

Lesley Dingle - Acquisition and Creation of Content

Daniel Bates - Visual Presentation, Technical Enhancement and Audio Editing

- 1 Which became an RAF Fighter Command airfield during the Battle of Britain.

- 2 UCL was founded in 1826 and King’s in 1829.

- 3 Harold Potter (1896-1951), Professor of English Law, University of London (1938-1951).

- 4 Glanville Llewelyn Williams (1911-97), Quain Professor of Jurisprudence, London University 1945-55; Jesus College, Cambridge; Rouse Ball Professor of English Law 1968-78.

- 5 Herbert Felix Jolowicz (1890-1954), Professor of Roman Law, University of London 1931-48, Regius Professor of Civil Law, University of Oxford, 1948-1954.

- 6 Professor Henry Arthur Hollond (1888-1974), Rouse Ball Professor of English Law 1943-50.

- 7 Professor Sir Hersch Lauterpacht (1897-1960). Judge at International Court of Justice 1954-60. Whewell Professor of International Law 1938-55.

- 8 Patrick William Duff (1901-1991), Regius Professor of Civil Law 1945-68.

- 9 Professor Emlyn Capel Stewart Wade (1895-1978), Downing Professor of the Laws of England 1945-62.

- 10 Professor Sir Percy Henry Winfield (1878-1953) Inaugural Rouse Ball Professor in English Law 1928-43.

- 11 Professor Sir Robert Yewdall Jennings (1913-2004), President International Court of Justice 1991-94. Whewell Professor of International Law, 1955-81.

- 12 T. Ellis Lewis (1900-1978), Librarian, Squire Law Library 1931-68.

- 13 Professor Sir Henry William Rawson Wade (1918-2004). Rouse Ball Professor of English Law, 1978-82. Master of Gonville & Caius 1976-88.

- 14 Professor Sir Arthur Llywellyn Armitage (1916-1984), President of Queens’ College (1958–70), Vice-Chancellor of the University of Manchester (1970-80).

- 15 R. N. Gooderson, St Catherine’s College.

- 16 J.W.A. Sidney Sussex

- 17 Mr Reginald Walter Michael (Mickey) Dias (1921-2009), Lecturer in Law, University of Cambridge (Jurisprudence & Tort) 1951-1986. Fellow Magdalene College. See:http://www.squire.law.cam.ac.uk/eminent_scholars/rwm_dias.php

- 18 John A. Hopkins, University Lecturer, 1968-2004, Downing College.

- 19 Charles John Hamson (1905-1987), Professor of Comparative Law 1953-73.

- 20 Sir David Glyndwr Tudor Williams (1930-2009), Rouse Ball Professor of English Law 1983-92, 1980-92.

- 21 Professor Kurt Lipstein (1909-2006), Professor of Comparative Law, University of Cambridge 1973-76. See:http://www.squire.law.cam.ac.uk/eminent_scholars/kurt_lipstein.php

- 22 Kenneth William Wedderburn (1927-2012). Baron Wedderburn of Charlton, Labour politician, lecturer in law at Cambridge, later Cassell Professor of Commercial Law.

- 23 Became a Liberal Party candidate for a Devon constituency

- 24 Later became Master in Chancery

- 25 John Waddingham Brunyate. For examples: F. W. Maitland, Equity: A Course of Lectures, 2d ed. 1936; The Legal Definition of Charity (1945) 61 Law Quarterly Review, 268 - 285

- 26 Much of this historical information comes from J. H. Baker, 1996. 750 Years of Law at Cambridge, Faculty of Law, 24pp.

- 27 He was the last "part time" librarian.

- 28 Clarence Staines, Senior Assistant Librarian Squire Law Library 1931-68.

- 29 Edmund "Teddy" W. Hill, (1904-1973), Library Assistant, Squire Law Library, 1920-71.

- 30 Millicent A. "Betty" Suckling (d. 1988). Mayor of Cambridge 1983-84.

- 31 Wilhelm Anton Friedrich Paul Steiner (1918-2003), Assistant Librarian, Squire Law Library 1959-68.

- 32 D. I. C. Ashton-Cross. (1964). St John’s College. Writer to His Majesty’s Signet, was assistant lecturer in 1936 and continued his association with the Faculty as lecturer until 1964.

- 33 Geoffrey Dawson Lane, Baron Lane AFC PC QC (1918 – 2005). Lord Chief Justice of England 1980-92.

- 34 Peter Zawada, Deputy Librarian, Squire Law Library 1997 -

- 35 Partly fuelled by anti-Vietnam War protests.

- 36 Professor Sir Henry William Rawson Wade (1918-2004). Professor of English Law, University of Oxford 1961-1976, Rouse Ball Professor of English Law 1978-1982.

- 37 E.g. Venn, J., Roberts, E. S. & Gross, E. J. 1897. Biographical history of Gonville and Caius college, 1349-1897; containing a list of all known members of the college from the foundation to the present time, with biographical notes. Volume: 2. G&C.

- 38 Joseph Bright Skemp (1910-1992), Professor of Greek Durham University (1950-73).

- 39 Julie Boucher, Faculty Administration 1986 -

- 40 Regina v. Page, 10 November 1953, [1954] 1 Q.B. 170 at 176

- 41 David. E. C. Yale, Emeritus Fellow in Law Christ’s College. Reader in English Legal History, Inner Temple, President of the Selden Society (1998-?).

- 42 Prichard, M. J. & Yale D. E. C. 1993, The Selden Society.

- 43 The Rolls of Oléron first formal statement of maritime law in NW Europe, promulgated by Eleanor of Aquitaine circa 1160.

- 44 2 LJCP (NS) 190

- 45 (1773) 2 W Bl 892; 96 ER 525.

- 46 Prichard, M. J. 1976. Scott V. Shepherd (1773) and the emergence of the tort of negligence. Delivered in the Old Hall of Lincoln's Inn, July 4th, 1973. Selden Society43pp.

- 47 Colin C. Turpin, (b. 1928- ). Emeritus Reader in Public Law.

- 48 In Denbighshire

- 49 Alfred Waterhouse (1830-1905), architect. Designed the Natural History Museum, Manchester Town Hall, Lime Street Station Liverpool, Oxbridge college work at Balliol, Jesus, Trinity, Pembroke and Girton. 1867 designed the New College Buildings for Gonville & Caius.

- 50 Francis Harry Compton Crick, (1916-2004). Co-discoverer with James Watson of the structure of DNA (February 1953), J.W. Kieckhefer Distinguished Research Professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

- 51 Francis Frith (1822-1898), pioneer photographer of national town- and land-scapes.

- 52 See the article by James Howell entitled "Michael Prichard and the Great Gate" in the online "Once a Caian", Issue 10, Michaelmass 2009.http://www.gonvilleandcaius.org/Document.Doc?id=178

- 53 James Dewey Watson, (b. 1928-) co-discoverer of the structure of DNA with Francis Crick. Director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), Long Island (1968-2007).

- 54 John Caius, (1510-1573), physician.

- 55 1348, by Edmund Gonville (d. 1351), Rector of Terrington St Clement in Norfolk.

- 56 A status finally extinguished in the Law of Property Act 1922.

Bibliography

Books

- Prichard MJ Scott v Shepherd (1773) and the Emergence of the Tort of NegligenceLondon Selden Society 1976 Selden Society Lectures 1973

- Prichard MJ (ed) Biographical History of Gonville and Caius College Canbridge Gonville and Caius College 1978

- Prichard MJ (ed) Hale and Fleetwood and Admiralty Jurisdiction London Selden Society 1993

Journals

- Army Act and Murder Abroad (1954) 1954 Cambridge Law Journal 232 – 241

- Nonsuit: A Premature Obituary (1960) 1960 Cambridge Law Journal 88

- Tort – Husband and Wife – Medical Expenses (1960) 1960 Cambridge Law Journal 153

- Malicious Prosecution – Fair Fame – Costs as Damage (1961) 1961 Cambridge Law Journal 171

- Perpetuities – Ulterior Limitations – Dependent or Independent (1962) Cambridge Law Journal 163

- Trespass, Case and the Rule in Williams v Holland (1964) 1964 Cambridge Law Journal 234

- Two Petty Perpetuity Puzzles (1969) 27 Cambridge Law Journal 284

- Trusts For Sale – The Nature of the Beneficiary’s Interest (1971) 29 Cambridge Law Journal 44

- The Matrimonial Castle (1973) 32 Cambridge Law Journal 227 – 230

- Joint Tenancies – Severance (1975) 34 Cambridge Law Journal 28 - 31

- Class Actions and Private Law Enforcement (1978) 27 University of New Brunswick Law Journal 5 – 17

- Registered Land – Trust For Sale – Actual Occupation (1979) 38 Cambridge Law Journal 23 – 26

- Joint Tenancy – Trust For Sale – Conversion (1979) 38 Cambridge Law Journal 251 - 254

- Registered Land – Overriding Interests – Actual Occupation (1979) 38 Cambridge Law Journal 254 – 257

- Registered Land – Overriding Interests – Actual Occupation (1980) 39 Cambridge Law Journal 243 - 246

- Crime at Sea: Admiralty Sessions and the Background to Later Colonial Jurisdiction (1984) 8 Dalhousie Law Journal 43 – 58

Book Reviews

- Bell HE, An Introduction to the History and Records of the Court of Wards and Liveries (1954) 12 Cambridge Law Journal 133 - 135

- Hake E, Epiekeia: A Discourse on Equity in Three Parts (1956) 14 Cambridge Law Journal 126 – 127

- Thorne SE (ed.) Readings and Moots at the Inns of Court in the Fifteenth Century. Volume I (1957) 15 Cambridge Law Journal 98 - 101

- Ogwen Williams W (ed.), Calendar of the Caernarvonshire Quarter Sessions Records Vol. 1 1541 – 1558 (1957) 15 Cambridge Law Journal 101 – 102

- Holdsworth W & Hanbury HG, A History of English Law, Seventh Edition (1957) 15 Cambridge Law Journal 107 - 109

- Robson R, The Attorney in Eighteenth-Century England (1960) 18 Cambridge Law Journal 242 - 245

- Plucknett TFT, Edward I and Criminal Law (1962) 20 Cambridge Law Journal 255 - 256

- Bowen CD, The Lion and the Throne: The Life and Times of Sir Edward Coke 1552 – 1634 (1967) 15 Cambridge Law Journal 249 - 251

- Harold Greville Hanbury, The Vinerian Chair and Legal Education (1960) 18 Cambridge Law Journal 121 – 122

- Holdsworth W & Hanbury HG, A History of English Law (1966) 24 Cambridge Law Journal 134 - 136

- Gilchrist Smith J, Emmet’s Notes on Perusing Titles and on Practical Conveyancing 15th Edition (1968) 26 Cambridge Law Journal 324 – 327

- Veall D, The Popular Movement For Law Reform 1640 – 1660 (1970) 28 Cambridge Law Journal 325 - 327

- Kerridge E, Agrarian Problems in the Sixteenth Century and After (1971) 29 Cambridge Law Journal 158 - 160

- Cockburn JS, A History of English Assizes 1558 – 1714 (1973) 32 Cambridge Law Journal 146 - 148

- Megarry R & Wade HWR, The Law of Real Property 4th Ed (1976) 35 Cambridge Law Journal 176 – 178

- Thorne SE, Bracton on the Laws and Customs of England, Volumes 1 & 2 (1970) 28 Cambridge Law Society 314 - 318

- Thorne SE & Woodbine GE (ed.) Bracton on the Laws and Customs of England, Volumes 3 & 4 (1978) 37 Cambridge Law Journal 167 - 169

- Arnold M, Green T, Scully S & White S (eds), On the Laws and Customs of England. Essays in Honour of Samuel E. Thorne (1982) 41 Cambridge Law Journal 180 – 181

- Simpson AWB, Cannibalism and the Common Law (1985) 44 Cambridge Law Journal 482 – 484

- Cockburn JS, Calendar of Assize Records. Home Circuit Indictments Elizabeth I and James I (1986) 45 Cambridge Law Review 519 - 521